[Belt&Road] A Sunnier India

In January 2016, representatives from 57 countries including India attended the launch of what Chinese President Xi Jinping called a “historic” initiative: the US$100 billion Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in Beijing. With China in the lead, the massive project focuses on boosting investment in infrastructure projects in Asia, rivalling the World Bank.

India, one of the member countries, is the bank’s second-biggest shareholder, with a contribution of US$8 billion, second only to China’s US$29.7 billion. A year on, India, one of the bank’s founding nations, is expected to be granted one of the first loans issued by AIIB as it works to raise US$500 million for solar power projects.

The AIIB investment is expected to bring a huge boost to the country’s fledgling solar sector.

For the most part, Asian economies are plagued by poor infrastructure, a lack of regional connectivity and minimal amenities in urban spaces. AIIB has been touted as a major powerhouse to address challenges that have stunted the growth prospects of several Asian economies. Electricity is still a luxury in many places in India: thousands of villages across various states still live in darkness, so expanding the solar sector is critically important.

Power Struggles

Several cities in India, including the capital New Delhi, have faced frequent power outages. In 2012, 20 of India’s states and New Delhi simultaneously fell into darkness when three of the country’s five power grids failed. Even cities and villages connected to the grid face frequent disruptions with per-capita electricity consumption in India at only a fourth of the global average.

In the 2012 incident, India’s northern grid was the first to fail, leaving an estimated 300 million people in the dark for up to two days. Traffic lights went out, causing massive jams, hospitals shut down and several trains stopped running in major cities. It was quickly followed by the eastern grid, which covers Kolkata, then the north eastern grid.

While massive power outages of this scale are not common, India has long been plagued by power problems, and rolling power-cuts are frequent across the country.

As the situation stands now, AIIB’s role is significant. The bank’s focus on funding renewable energy projects like solar should help alleviate fears that its relaxed lending criteria could lead to funding of dirty fuel and coal projects in developing economies in Asia. With many nations in a rush to increase their energy production to keep pace with growing demand, massive environmental damage remains a constant fear.

Through its investments, the Asian lender will strive to promote interconnectivity and economic development in the region by developing infrastructure and other productive sectors. Indian states like Madhya Pradesh have already approached AIIB for support for major rural water projects in the state, and its involvement is expected to expand over time.

India’s solar power ambitions are growing as well. Renewable-energy financing in India faces a multitude of challenges such as high interest rates, conservative risk-assessment norms and lack of long-term debt instruments. Additionally, the country’s commercial banks have been very slow to warm to the sector. Funding from AIIB is crucial for India to reach its goals for its budding solar sector.

India is also in talks with the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, Germany’s KfW and the New Development Bank, a joint project of big emerging economies of the BRICS bloc, to raise more than US$3 billion in the financial year starting April 1. Frequent power cuts impact economic activity, and because India is one of the fastest-growing economies in the world, competing with other powerhouses like China, quickly resolving its power issues is an urgent task.

AIIB, led by Jin Liqun, is looked at as a major powerhouse that will address infrastructure challenges across several Asian countries. CFP

Acknowledging the urgency, the Indian government has moved fast to increase power generation capacity. In 2015, India was the third-largest producer (after China and the U.S.) and fourth-largest consumer of electricity in the world, with the installed power capacity reaching 306.36 GW by September 2016. India also has the fifth-largest installed capacity in the world.

Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, came to power in 2014 on a promise of providing reliable power by 2019. The price of electricity is heavily regulated in India, where states provide electricity far below market costs and take up huge losses. Despite increasing its power generation capacity, the state discoms (distribution companies) face financial troubles, with an estimated US$70 billion of accumulated debt and no way to pay generators; this has been a major difficulty for India in supplying reliable electricity to its vast population.

India’s power demand is estimated to grow at an average rate of 5.2 percent during the ten years between 2014 and 2024, according to a report by Tata Power. Currently, India requires 1,068,923 million units of electricity annually but the supply falls short by 3.6 percent.

Most of this demand cannot be met via traditional energy sources. India’s coal-fed power plants, which contribute to nearly 60 percent of total production, have been grappling with periodic fuel shortages. Domestic production of coal hasn’t quite kept pace with demand, which has aggravated the situation, considering the expensive price of imported coal.

While Mr Modi has made universal access to electricity a key platform of his administration, he has also promised to participate in international efforts to limit climate change.

India is currently one of the world’s largest emitters of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases and hopes to meet its electricity demands without dramatically increasing carbon emissions. The government’s focus on renewable energy partially stems from the fact that India imports 80 percent of its crude oil and 18 percent of its natural gas needs, leaving the country with an energy import bill of around US$150 billion.

Solar Sunrise

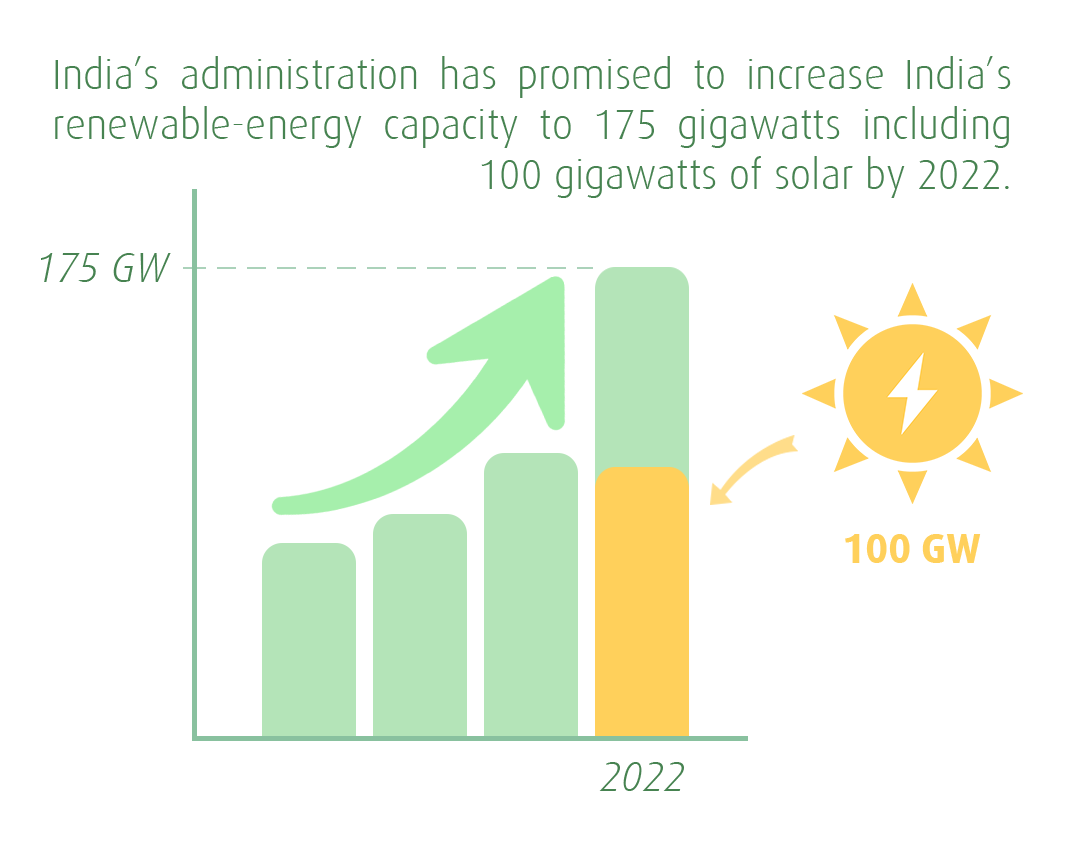

The Modi government recently approved an extraordinarily ambitious plan for India’s solar sector. Among other plans, the administration has promised to increase India’s renewable energy capacity to 175 gigawatts including 100 gigawatts of solar by 2022, with a target of attracting a staggering US$100 billion into the sector over the next seven years.

This comes even alongside a steady decline in solar power prices - thanks to cheaper solar panels and financing costs - which has made the sector increasingly attractive to investors. By 2019, according to estimates, India could achieve grid parity between solar and conventional energy sources.

Geographically, India is quite fit for solar – it receives an average of almost 300 sunny days a year, the potential for 5,000 trillion kilowatts of power. India is both densely populated and has high solar insolation, since it is conveniently located near the equator.

India’s solar sector recently turned a corner after a low bid of 2.97 rupees per kilowatt-hour (kWh) won the contract to build a 750 megawatt (MW) plant at Rewa in Madhya Pradesh. For India, solar power could one day cost less than power from conventional sources.

Major Challenges

Despite efforts to increase investment in the solar sector, big challenges remain. India’s biggest solar power project stalled when the state soliciting bids from generators admitted it couldn’t buy energy at the prices it had agreed on.

Several domestic and overseas clean-energy companies have reported delayed payments for several months – when marquee investors see more risks, India’s green ambitions could be jeopardized.

The biggest issue hindering the development of renewable energy investment in India is the health of public electricity distribution utilities, a hurdle that has been identified as one of the most crucial to overcome for Modi’s climate pledge to meet the solar generation capacity target.

State-owned power retailers in India absorbed combined losses of 3.84 trillion rupees as of March 2015 per a report by KPMG. These losses evidence that discoms can’t supply reliable electricity of any form – whether conventional or renewable – to satisfy expected demand, nor can they add more customers. Reversing these trends will require radical transformations in two main areas: how India produces electricity and how it distributes it. It is crucial for India’s fast-growing economy to get its solar power thrust right and support its growing population with reliable electricity without relying so heavily on coal. And with a boost from AIIB, India’s solar ambitions look significantly sunnier.

The author is a freelance Indian business journalist. She has covered business and finance for Hindu Business Line, reporting on topics such as banking, insurance, education and healthcare. She currently also works as a communications consultant for Bajaj Allianz General Insurance.