China and India: Building a Shared Future

China and India are two peer civilizations which today are two of the world’s largest and fastest-growing economies as well as rapidly transforming large societies with system-shaping capabilities. Their potential in determining the future of human society is widely recognized today and their successes lie in merging their efforts into joint strategies for global transformation. Their cooperation can accelerate the pace of comprehensive human development, a phenomenon which can already be seen inside these two societies as well as in their immediate peripheries. The consequent shift of global focus from the north Atlantic to Asia-Pacific has since unleashed new discourse on the changing nature of global geopolitics with Chinese and Indian experts contributing to emerging innovative and out-of-the-box narratives. At the very least, the promise of their potential provides China and India an exciting historic opportunity to work together to build a community with a shared future for humanity.

China-India relations have thus become one of the most important bilateral relations in the world. Recent years have indeed brought promising signs of growing mutual coordination between New Delhi and Beijing. This can be seen in increasing coordination on issues like climate change, energy security and anti-terrorism through mechanisms like the G20, BRICS, SCO and many other multilateral forums where both China and India now coordinate their stances and strategies.

This year marks the 40th anniversary of China’s reform and opening up. While this moment is particularly significant for China, it also provides a very important opportunity to examine the transformation of the China-India relationship over the decades and seek insight on their possible future trajectories.

Return to Rapprochement

Without a doubt, the indelible imprint of their colonial and Cold War legacies remains critical in determining their mutual perceptions and policies. Much effort was devoted to fighting their colonial legacies of divisiveness that were further reinforced by Cold War dynamics that saw China and India on opposite sides of the East-West divide.

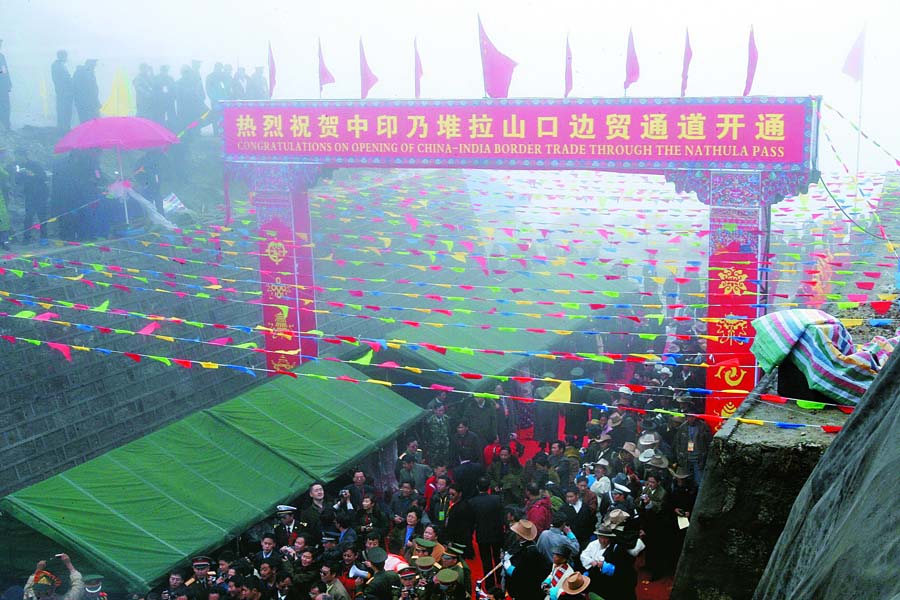

The process of reconciliation, which began in the early 1970s, was enduring even though it was fragmented and often peripheral. To keep things moving forward, the axiom to focus on agreeing on agreeables first emerged. This was the time when China was undergoing historic upheavals in internal affairs, and India declared an internal emergency in 1975. However, starting in the early 1980s, both sides discovered trade to show potential to build mutual understanding and trust. Among some historic initiatives, the breakthrough visit by young Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in December 1988 provided a much needed reset for bilateral relations. In the early 1990s, bilateral trade emerged as the most agreeable and reliable pillar of their newfound rapprochement, and focus was placed on building mutual confidence. This provided a very encouraging political and geopolitical climate that facilitated the two confidence-building agreements signed in 1991 and 1996 during historic visits to India by Premier Li Peng and President Jiang Zemin, respectively. These groundbreaking visits laid foundations for strong China-India relations that launched the trend of Chinese leaders making India-specific visits not combined with other countries. This period also saw the two sides set up various bilateral consultative mechanisms including their most enduring joint working group on the boundary question, which became the default forum to discuss all important issues related to ensuring mutual peace and security.

November 21, 1988: Deng Xiaoping meets with Prime Minister of India Rajiv Gandhi at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. During the meeting, Deng said that China and India should forget about the past and focus on the future, and that there is no reason for the two countries to be unfriendly to each other. CFB

The 1990s was the decade of China’s unprecedented rise. It was also a period in which India launched its own experiment with opening up and structural reforms. By then, Beijing’s decade-long experiment with opening up and economic reforms had presented to the world a whole new realm of inter-state relations. China was building strong economic relations with all countries, including its so-called adversaries. This was to become China’s magic trick to avoid Graham Allison’s Thucydides Trap thesis and render Western narratives of China threat theory ineffective. This was an era in which both China and India joined a whole range of regional forums such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and many more. Quickly, China and India began working together in regional forums to address regional issues. In the early 1990s, China joined a whole range of international forums in which India was already a member. These moves enhanced bilateral trade and deepened interactions which further facilitated improvements in mutual understanding and trust. This trend was briefly disrupted by nuclear tests by India and Pakistan in May 1998, but both China and India soon returned to the dialogue table. This rapprochement was accelerated again by the terrorist attacks of September 2001. Indeed, since the late 1990s, there has been growing consciousness on both sides that multilateralism is the only way to resolve security and development challenges.

Rising China, Emerging India

The new millennium has heralded China’s emergence as the world’s second largest economy and India as the fifth largest. Underlining their global engagement has become a new form of activism for overseas Chinese and Indians who are empowered by their countries emerging as major markets, so they become new donors and investors. Both countries are now involved in major third country projects. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has seen India participating in agencies like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, BRICS New Development Bank and Shanghai Cooperation Organization as well as projects like the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor. Another proposal for a China-Nepal-India Cultural Corridor is currently under consideration. China’s BRI has been seen by some in India as a new contentious point. Some media outlets in India have discussed boycotting the BRI. New Delhi, however, has only been absent from one Belt and Road forum in May 2017 and officially objects only to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Indirectly, India has shown concern for the BRI enhancing Beijing’s access and influence amongst India’s immediate neighbors and becoming increasingly present in the Indian Ocean. But the Indian Ocean has also welcomed the Chinese and Indian navies to hold joint naval exercises, and joint anti-piracy operations were conducted in the Gulf of Aden. It is important to note the strong equilibrium of this mosaic of cooperation and that contestations have not been allowed to derail interactions.

It has become clear that increasing engagement at multilateral levels has produced a positive impact on bilateral relations. With a rising China and an emerging India expanding their respective focus in space and time, they are becoming capable of placing various irritants in perspective and seeking diplomatic solutions to standoffs and deadlocks. It has been especially encouraging that President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Narendra Modi—both decisive, ambitious and energetic leaders—have built and showcased real personal camaraderie. Their repeated interactions at various multilateral forums have provided opportunities to address bilateral matters without any pressures of public expectations or the media seeking details of bilateral outcomes. This method was successfully applied during the 2017 Dong Lang (Doklam) standoff when a series of bilateral meetings on the sidelines of successive multilateral interactions in the run up to the BRICS summit in Xiamen helped resolve border tensions. And then the informal summit between Modi and Xi in April of this year is now credited for providing another reset for China-India relations, which are now guided by the so-called Wuhan Spirit of coordination and cooperation.

The Way Forward

While the China-India border dispute remains the most enduring and complicated problem hindering bilateral relations, other issues can be resolved much faster to create a better atmosphere for addressing more difficult knots. The enduring and formidable trade deficit reaching nearly US$60 billion of bilateral trade of US$84.44 billion in 2017 is one. Recent moves by China to allow imports of India’s non-basmati rice and sugar provide a promising start for China to appreciate the value of maintaining balanced trade to ensure faster growth in mutual economic engagement. Recently, China’s investment in India also witnessed a rapid rise. China’s investments in India’s manufacturing sector will not only reduce the need for imports from China but also make India’s exports competitive to bridge the trade deficit. The second most important initiative has been revival of Hand-in-Hand anti-terrorism exercises and exchange of officers from training institutions. India has likewise sought to address China’s various sensitivities on issues like the Indo-Pacific or the Quartet of U.S.-Japan-India-Australia.

The uninterrupted flow of regular interactions at all levels, especially between President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is now providing promise for greater coordination which is creating grounds for greater cooperation in maximizing mutual peace and prosperity and enhancing efficacy of contributions transforming global governance structures.

The author is a professor with the School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi and an adjunct senior fellow at the Charhar Institute, Beijing.