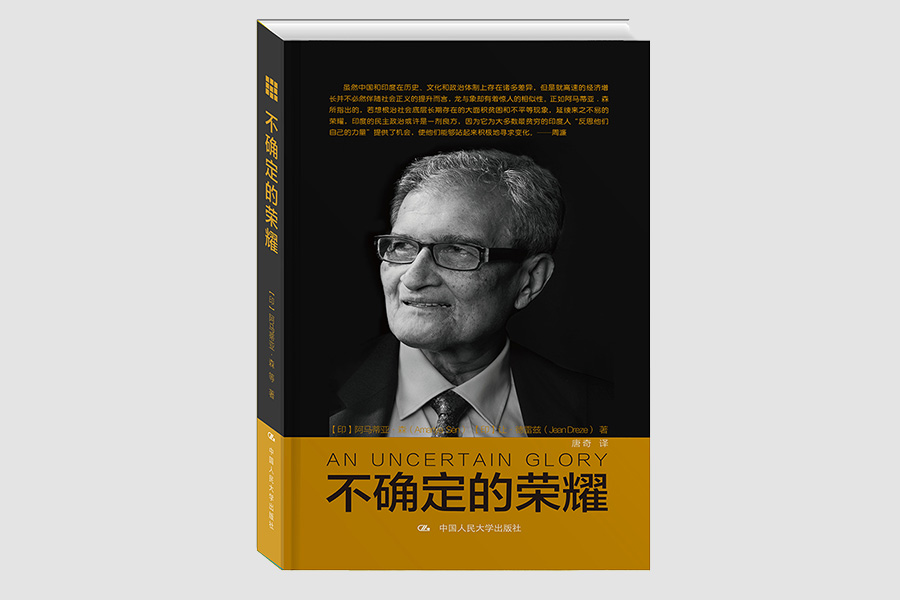

Book: An Uncertain Glory

An Uncertain Glory, a book jointly produced by the world-renowned economist Amartya Sen and his long-time partner Jean Drèze, was first published in 2013. Sen, who received the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 1998 for his contribution to welfare economics, and though in his eighties, he still pursues social fairness with his pen.

The authors raise the question of “Does high-speed growth really create a new India?” at the beginning of the book. The answer is uncertain, which can be “Yes” or “No” at the same time, because today’s India is “half in California, and other half in sub-Saharan Africa.” On the one hand, India has maintained an enviably high economic growth for more than a decade. On the other hand, it possesses a disappointing Human Development Index (HDI). The index is even worse than that of Bangladesh, whose per-capita income is only half of India’s. At the same time, in India, the gap between the privileged classes and the common people is widening.

With a comparative perspective, the book examines the different approaches adopted by various countries and India’s different states, and the different results they get respectively in fields such as public education, healthcare, and poverty alleviation. It asserts that all of India’s policy mistakes in these fields stem from imperfect democracy, and imperfect democracy is largely the result of the inequality existing in Indian society.

The book believes that few countries in the world are like India, which needs to fight against inequalities at multiple levels, including large-scale economic inequality, serious discrimination on grounds of caste, social class, and gender. In a social environment which lacks public reason like in India, the fight is doomed to be a one-sided game. In India, different groups possess extremely unequal rights of speech and influence, while media focus is always on the elite, the privileged, and the rich, and pays little attention to the interests of the poor. Indian Parliament also fails to attach importance to the interests of the poor regarding public revenue allocation. On the one hand, the government was reluctant to spend an extra of Rs 270 billion to provide food for the starving poor. On the other hand, it generously cut down import tariff of Rs 570 billion on diamonds and gold. Moreover, since cultural, education, and healthcare services provided by the government are hard to obtain and difficult to ensure guaranteed quality for the poor, their accesses to a better life have been blocked; which leaves them perpetually in a situation full of deprivations.

How to solve these problems? Patiently waiting for the overflow effect that eventually will come one day? This is definitely not the answer from Sen, a scholar who combined economics with moral philosophy to create welfare economics. However, the “constructive reform” on India’s politics proposed by Sen also calls for an investment of abundant time. Media need to be more conscientious and courageous to shake off the narrow-minded “elite” perspective. Society needs to rebuild public reason through extensive discussions on public issues, and the poor need to establish their own political organization by using their new political identities. Looking at the social achievements in Himachal Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala, reform is evident. But still, many things need to be done step by step.

In terms of arguments, the book provides valuable quantitative and qualitative analyses of Indian policies on public education and health service, and makes comparisons with those in China. Some of India’s experiences can be used as reference for China’s reform in relevant fields. One basic viewpoint of the book is that although private capital can play an active role in providing social public goods, the government still needs to shoulder major responsibilities.

Four decades ago, Sen’s renowned work Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation revealed that it is not food shortage, but rather the deprived exchange entitlement caused by social inequality, that have cost people’s lives during famines. Today, An Uncertain Glory tells readers that social inequalities still exist in a “prosperous” India, and are becoming even more shocking and unbearable.

When it is published in China, the book omits its original edition’s subhead “India and Its Contradictions.” Although these contradictions are exhibited in various forms, they all stem from social inequalities. Because of these contradictions, India’s glory brought about by economic growth becomes somehow uncertain, just like a sunny day can be ruined by an unexpected downpour at any time. I think sticking to its original name will be more accurate and complete in terms of conveying the authors’ ideas.

The author is the associate researcher with the National Institute of International Strategy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.