China’s 2017 Economic Prospects

Last year marked the beginning of China’s 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020). Amidst domestic worries in various sectors, the Chinese economy made a solid start and continued to contribute positively to world economic growth. In 2017, China will face even more complicated and faster-changing domestic and international situations, with increasing uncertainty. Against this backdrop, whether China can maintain its comparatively high economic growth rate of more than 6.5 percent has become a question of global interest.

2016 Economic Performance

To address serious issues and domestic problems plaguing China’s economy, the government adapted to the new normal of economic development in 2016, committed to a new innovative, coordinated, green, open and shared development model, and pushed supply-side structural reform to successfully meet major projected goals for economic growth and set a solid foundation for accomplishing the building of a moderately prosperous society in all respects.

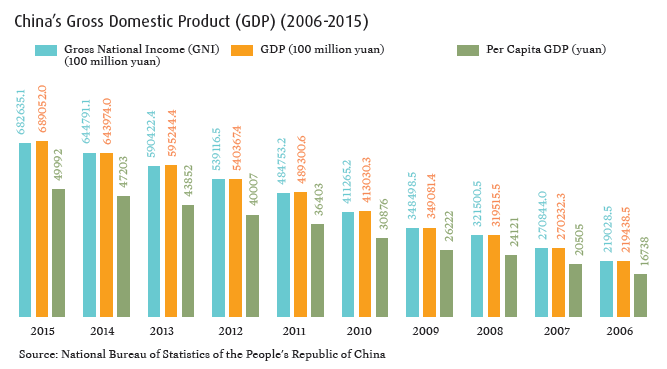

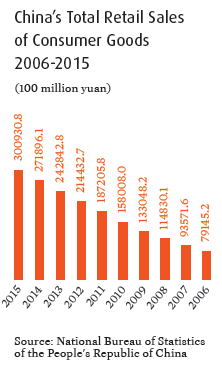

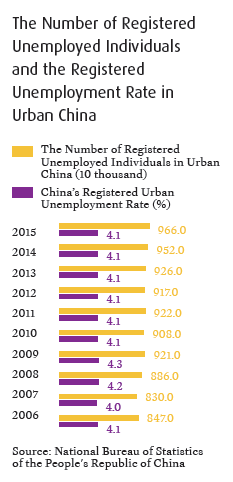

The economy operated within an appropriate range, as manifested in “four stabilities and one decline.” The first stability was growth. China’s GDP growth rate in the first three quarters of 2016 averaged 6.7 percent, as did the projected annual growth rate. The figure landed right in the middle of the economic goal of 6.5 to 7 percent set in early 2016, indicating that China’s economy will now grow in an L-shaped path. The second stability was employment. The first three quarters of 2016 witnessed the creation of 10.67 million urban jobs, which met the annual goal of 10 million ahead of schedule. And this figure was expected to surpass 13 million by the end of 2016. The third was stability of commodities prices. In 2016, China’s commodities prices rose around the start and end of the year, but stayed low at other times. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) from January to November increased 2.2 percent on a year-on-year basis, lower than the control objective of 3 percent. The fourth was the stability in consumption. The country’s total retail sales of consumer products from January to November 2016 increased 10.4 percent year-on-year, slightly lower than the growth rate of the same period in 2015. China has become the world’s second largest consumer market and facilitates the greatest total volume of e-commerce in the world. The one decline refers to both exports and imports. From January to November 2016, China’s total volume of imports and exports dropped 1.2 percent year-on-year, with exports falling by 1.8 percent and imports by 0.3 percent. The drop tended to narrow month by month.

China Iron and Steel Industry Association asserts that in 2017, it will further regulate the market order of imported iron ore trading, strictly implement an iron ore import agent system, and set the price decided by both buyers and suppliers as the national uniform price for 2017 imported iron ore in China. [CFP]

Economic quality and efficacy improved as well as corporate performance. From January to November 2016, added value of industrial enterprises above a designated size increased by 6.2 percent on a year-on-year basis. The coal industry saw profits double in 2016. The iron and steel industry reaped profits of more than 30 billion yuan in 2016 after a deficit of over 50 billion yuan in 2015. In September 2016, the Producer Price Index for Industrial Products (PPI) went positive and has since increased month by month to 3.3 percent in November. With PPI going positive for the first time in 54 months, the Chinese economy has avoided deflation.

The economic structure has been upgraded. Since 2010, the growth rate of China’s service sector has surpassed that of industry. In 2013, the share of the service sector in China’s national economy first surpassed that of secondary industry, promoting the transformation of the economic structure from investment and export-driven to consumption-driven and of industrial structure from industry-dominated to service-sector-dominated. In the first three quarters of 2016, final consumption contributed 71 percent of economic growth, up 13.3 percent over the same period of 2015. After structural adjustment, the proportions of the three industries in relation to the total economy are 8.5, 39 and 51.5, respectively.

The pace for the changing of economic growth engines is accelerating. In 2016, traditional industries, including iron and steel, coal, nonferrous metal, building materials and petrochemicals, continued to see declining growth rates. Emerging industries such as high-end equipment, robotics, energy conservation, environmental protection, new energy automobiles, and new internet operational models and service industries such as healthcare, senior care, tourism, culture and sports are developing at breakneck speed. In the first three quarters of 2016, added value for strategic emerging industries, as well as new and high technology industries, increased by more than 10 percent, four percentage points higher than the industrial growth rate. More than 4 million enterprises registered in the first three quarters of 2016, an increase of 27 percent on a year-on-year basis. The majority of these enterprises are in the service industries such as data delivery, software, information services, finance, culture, sports, entertainment, education, health, and social work.

Problems and Risks

At present, downward pressure on the Chinese economy continues to mount, and many serious issues and deep-rooted domestic problems remain unresolved. The accompanying financial risks should not be ignored.

The weak export outlook presents a daunting challenge. In recent years, soaring labor costs have decimated China’s low cost competitive advantage on exports. Labor-intensive industries are relocating to India and Southeast Asian countries where labor costs are lower. China’s market share of traditional exports has gradually shifted to those countries. Although China’s currency, the RMB, depreciated significantly against the U.S. dollar in the second half of 2015, commodities exports didn’t increase and even decreased most months. China’s current export mode, with traditional industrial products at the core, cannot be sustained. If China cannot quickly improve the structure and quality of exported products, further export decline is inevitable. The year 2014 was likely the peak of China’s exports as a proportion of the global total.

China’s real economy, especially traditional industries, is still facing tremendous difficulties. With increases in China’s resource and environmental costs as well as burdens including comparatively high taxes, fees and social security payments, the operational costs of China’s enterprises are rapidly rising and profits are declining drastically. Many private, medium and small enterprises in particular are facing operational difficulties and lack confidence in future development, resulting in a sharp decrease in private investment. Private investment in the first three quarters of 2016 increased by only 3.1 percent on a year-on- year basis, far below the growth rate of 10.2 percent in the same period of 2015. Since private investments account for more than 60 percent of China’s total, if the situation doesn’t change, China’s real economy will lose development momentum and international competitiveness. In August 2015, the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) released The Shifting Economics of Global Manufacturing. In the report, BCG opined that while China’s manufacturing cost advantage over the U.S. was 13.5 percent in 2004, the figure shrunk to 4 percent in 2014, almost a 1 percent loss every year. It is estimated that by 2018, manufacturing costs in the U.S. will be lower than in China by 2 to 3 percent.

Financial risks are still mounting along with other hidden dangers. In great contrast with the sluggish real economy, the virtual economy and asset price bubbles have been growing. Although no major financial risks have been triggered yet, potential dangers should not be ignored. Like the world’s major developed economies, China is in an era of abundant liquidity. Massive sums, or “hot money,” are making their way into equity, real estate, bonds, and foreign exchange markets. Poor handling of this situation could easily lead to a chain reaction in the market. The ups and downs of China’s stock market in early 2016 and on the foreign exchange market in recent months have illustrated this point.

Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba made a record 120.7 billion yuan from sales on its major shopping websites in just 24 hours on 2016 Singles’ Day (November 11), a record amount in global retail for any single day. Moreover, during this spending spree, the wireless transaction volume accounted for 82 percent of the total. [CFP]

Based on the current situation, China’s financial risks are primarily located in the following sectors:

First, the risk of bad debt increases when capacity drops. Preliminary statistics show that China’s four industries with severe overcapacity — coal, steel, non-ferrous metals, and cement — have accumulated a total debt of 5.4 trillion yuan. If this situation is not properly addressed, the risk of large-scale debt default will rise. Only a default rate of 30 percent will drive up the non-performing loan ratio of Chinese commercial banks to 1.5 percent and further affect the credibility of the country’s entire financial system.

Second, polarization risk in the real estate market has been exacerbated by China’s surplus of unsold homes. A series of policies aimed at clearing the property glut across China has further boosted housing prices in first-tier cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen as well as in some more developed second-tier cities. In such cities, the housing price-to-income ratio measures well above 10 and even as high as 20, indicating a large housing bubble. Still, real estate sales in most third and fourth-tier Chinese cities were poor, and the real estate surplus is yet to be solved. Incidents like capital chain breaks and property developers abandoning half-finished projects are common.

Third is the risk of high leverage ratio on debts. Since the 2008 global economic recession, China, and its enterprises especially, have witnessed a rapid growth in leverage ratio. By the end of 2015, China’s debt-to- GDP ratio (finance sector excluded) reached 250 percent, which is quite high compared to the rest of the world. Although government debt and household debt accounted for only 43 percent and less than 40 percent, respectively, well within appropriate ranges, enterprise debt reached 166 percent, the highest among the world’s major economies. China’s enterprise debt measured 1.7 times the average in developed countries and 3.5 times the average in emerging markets.

Fourth is fluctuation risk on the currency market brought about by devaluation expectations on the RMB. In 2015, China saw its first net capital outflow. In 2016, the country’s capital outflow further increased by a large margin. From January to November in 2016, China’s investments in foreign countries were valued at about US$162 billion, an increase of more than 55 percent over the same period of 2015. With the progress of the Belt and Road Initiative, Chinese enterprises are venturing to foreign lands along with investments and acquisitions. Besides, some foreign capitals are withdrawing from China and transferring to other countries. Thus, China’s foreign exchange market has shouldered great pressure from fund outflow and RMB devaluation.

China’s Economic Outlook For 2017

In 2017, the international environment and its relation to China’s economy are bound to become more complicated by increasing uncertainty. The most glaring uncertainty lies with foreign and domestic policy adjustments to come from U.S. President Donald Trump now that he has formally taken office. Actually, Trump’s policy adjustments present both pros and cons for China. On the positive side, Trump promised to increase infrastructure investment and cut taxes during his campaign, which will increase U.S. demand, stimulate investment, and promote imports, further stimulating the economic growth of the U.S. and the world while improving China’s environment for international demand.

However, on the flip side, Trump could enact a series of protective measures against Chinese exports to the U.S., potentially levying prohibitive duties, which would lead to greater economic and trade friction between the two countries.

Although the Chinese economy is facing challenges and risks domestically, its comparatively high growth rate creates many advantages. First, China’s deepened reforms will create a more favorable environment for entrepreneurship and innovation, releasing the reform dividend. Second, China’s further implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative will promote a heavier volume of imports at advanced levels as well as exports through various channels, re-shaping the opening-up dividend. Third, the comprehensive implementation of China’s innovation-driven development strategy will kindle enthusiasm from the world’s largest group of engineers and university students, cultivating a new professional dividend. Fourth, the implementation of regional development strategies such as the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei integration initiative and the Yangtze River Economic Belt initiative will reinforce cooperation between more developed and less developed areas in China, building up the regional development dividend. Fifth, progress in new urbanization will effectively enhance the labor productivity of around 100 million people with rural household registration living in China’s urban areas, enlarging the urbanization dividend. Based on the five dividends, the Chinese economy in 2017 will maintain comparatively high growth with an expected rate of 6.5 percent or greater.

In 2016, the Chinese government launched a number of measures and supporting policies for supply-side structural reform. The country has obtained positive results in terms of decreasing capacity, reducing the volume of unsold homes and reducing costs. Annual goals of cutting excessive capacity of 45 million tons of steel and 250 million tons of coal have been completed ahead of schedule, fostering the recovery of business activity and improved business operations. The country’s unsold residential floor space has dropped for seven consecutive months, and replacement of the business tax with value added tax (VAT) has reduced costs for Chinese enterprises by 500 billion yuan. However, the country’s efforts to reduce leverage and improve weak links need further analysis.

Promoting supply-side structural reform is a key part of China’s 13th Five-Year Plan. This year will bring deepened supply-side structural reform. The 2016 Central Economic Work Conference, which just concluded in December, mandated deep supply-side structural reform in 2017, which means that reform will be further intensified in the coming year.

In terms of solving overcapacity, China has already issued two general documents on the steel and coal industries, and eight supporting documents on rewards and subsidies, taxation, finance, employee resettlement, land resources, environmental protection, quality, and security. The key work for 2017 remains policy implementation, especially employee resettlement.

In terms of reducing the number of unsold homes, instead of relying on administrative measures and rapidly changing regulatory policies as in 2016, China in 2017 will focus on exploring a long-term mechanism to boost the healthy development of the real estate industry.

In terms of reducing leverage, China will transform banks’ non-performing loans to enterprises into equity held by asset management institutions through debt-for-equity swaps. In terms of reducing costs, China will improve its practice of replacing business tax with VAT and at the same time further reduce taxes and fees, especially reducing the VAT rate on the manufacturing industry.

In terms of improving weak links, China will increase its investment in agriculture, poverty alleviation, improving public livelihood, ecological protection and innovation in 2017.

In terms of the country’s macroeconomic policy in 2017, China will continue to adhere to a proactive fiscal policy and a prudent monetary policy, but with a different intensity. Fiscal policy will be even more proactive. The Chinese government will raise spending by increasing its budget deficit, but at the same time, reduce the cost of the real economy and promote upgrades of the industrial structure through structural tax cuts. China’s monetary policy will remain prudent and neutral in 2017. Since expectations about the country’s inflation in 2017 are on the rise, the country’s broad measure of money supply (M2) needs to avoid being too loose or too tight to keep commodity prices within a reasonable range. It is expected that the M2 growth rate in China will stay at 12 percent in 2017, the same as 2016. Prudent monetary policy fosters stable exchange rates, and the Chinese government will keep the RMB stable in 2017 to maintain the balance of increased exports and capital flow.

The author serves as director of the Institute of Industrial and Technological Economics under the Chinese Academy of Macroeconomic Research.