Doklam Standoff: India’s Obsession with “Absolute Security”

In mid-June, Indian troops crossed into China at the Sikkim section of the border, followed by an Indian attempt to obstruct ongoing construction activities by the Chinese frontier forces in China’s Doklam area, instigating a standoff with Chinese troops. The fundamental reason for this confrontation is Indian strategists’, particularly Modi’s policy consultants’, obsession with “absolute security.” Thus, the Indian government frequently tackles its imaginary security implications as real threats, and even goes so far as to interfere in internal and foreign affairs of other countries.

The Modi administration’s hostile attitude towards China and its accompanying policies has reduced the China-India relations to a serious status of strategic distrust, which may even jeopardize the previous cooperative-competitive China-India relations to a total “adversarial relationship.”

In terms of the Doklam standoff, Modi administration has made three major mistakes:

First, India damages the existing consensus and already-signed treaty at its own will. The Sikkim section of the China-India boundary was delimited in 1890 in the Convention Between Great Britain and China Relating to Sikkim and Tibet, and the boundary demarcation is recognized by both China and India. The successive Indian governments have repeatedly confirmed in the past that it recognizes this part of the boundary, and no disputes previously existed. Based on this treaty, China constructed border roads within its own territory. Also based on this treaty, India built fortifications in the Sikkim section of the China-India boundary. Now, India’s entrenchment and abundant blockhouses in this region has overwhelming superiority over China in terms of border defense. Actually, India’s unconventional border defense construction has already seriously violated the Agreement Between the Government of the People's Republic of China and the Government of the Republic of India on the Maintenance of Peace and Tranquility Along the Line of Actual Control in the China-India Border Areas signed in 1993 and the Agreement Between the Government of the People's Republic of China and the Government of the Republic of India on Confidence Building Measures in the Military Field Along the Line of Actual Control in the China-India Border Areas signed in 1996. Thus, talking about border defense construction threats, it is India’s unconventional border defense construction which has posed serious real threats to China’s security.

The current standoff in China’s Doklam area is caused by the Indian troops’ trespassing of the Chinese territory. It is a breach of the 1890 convention and a gross violation of the international law, going against the promissory estoppel. It also completely contradicts to Modi administration’s call of establishing an international order “based on international rules.” Even if India believes that the 1890 convention was not fair, it should never selectively accept and break the convention unilaterally. It can never claim rights with a map produced by Britain years later and tread the 1890 treaty at its own will.

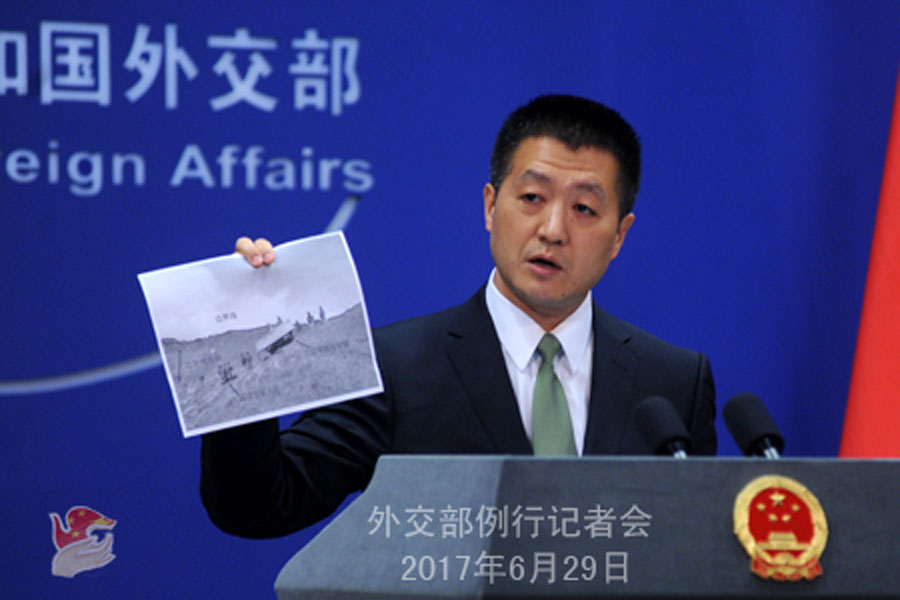

We can take a look of the map. After the 1890 convention was signed, the British were soon dissatisfied with the first clause in the treaty. While the clause states that “the boundary of Sikkim and Tibet shall be the crest of the mountain range separating the waters flowing into the Sikkim Teesta and its affluents from the waters flowing into the Tibetan Mochu and northwards into other rivers of Tibet. The line commences at Mount Gipmochi on the Bhutan frontier, and follows the above-mentioned water-parting to the point where it meets Nepal territory,” British believed that the features of Mount Gipmochi as the starting point of the boundary were not obvious. Thus, in a time between 1907 and 1913, Britain published a map showing the boundary started at Batang La, six kilometers north of Mount Gimpochi, and believed that its features were more evident as the dividing crest.

India’s basis for trespassing into the Chinese territory is probably from the map produced by Britain. One of the reasons offered by Modi administration is that India, China, and Bhutan have different opinions on the tri-junction. India and Bhutan hold that it is more reasonable to place the southeast starting point of the Sikkim section of China-India boundary at Batang La rather than Mount Gimpochi. Thus, the Indian troops’ “entry” into Doklam is legal. However, although the border between China and Bhutan is yet to be demarcated due to the obstructions set by India, it is clear that Mount Gipmochi is located south to Doklam and Doklam belongs to China. In the 1890 convention, the tri-junction among China, India, and Bhutan is Mount Gimpochi, which was put down in black and white. Although this point has no specific latitude and longitude due to the undemarcated boundary between China and Bhutan, but a point is a point. It can never be expanded to a plane. On this issue, India quibbles due to its concern on its own safety.

But most importantly, Britain’s producing of the map is undoubtedly a unilateral action. The map is not a necessary part of the 1890 convention, and China has no obligation to abide by it. Indian troops’ trespassing into the Chinese territory has in effect turned the 1890 convention invalid, and made the China-India boundary question even more complicated. Actually, the Sikkim section, as the mutually-recognized boundary section, facilitates the border trade between China and India, and offered a safer route for Indian pilgrims to Tibet. However, the Doklam standoff not only made the whole China-India boundary undemarcated, influenced the bilateral trade and the route for Indian pilgrims to Tibet, but also granted the Chinese government the right to renegotiate the legal status of Sikkim and its administrative division. China has the right to ask India to restore the Sikkim section of the border to the 1794 boundary decided by China’s Tibet and Sikkim. Sikkim, which was known as Dremojong then, was a vassal state of Tibet although it was independent back then.

Second, India uses the excuse of “own security concern” to interfere the domestic and foreign affairs of its neighboring countries. According to the 1890 convention, the Doklam region is a part of Chinese territory and since then, Doklam has always been under China’s effective jurisdiction. Because the Bhutanese government objects to the southeastern end defined in the 1890 convention that defines the tri-junction of the three countries, China and Bhutan have at most some disagreements over the Doklam area. However, not until 2000, when the 14th round of talks was held, did Bhutan make clear its understanding of the alignment of the boundary in the Doklam area. Even then, the decision seemed to be inspired by pressure from India. This boundary issue should involve only two countries: China and Bhutan. India is not a party with a claim. However, because “Bhutan claims sovereignty over Doklam area” and “to protect Bhutan,” India illegally crossed the China-India border and entered Chinese territory. Moreover, in its reaction to the incident, Bhutan had no idea what India was planning to do. So, India, under the guise of justice, sabotages Bhutan’s foreign affairs and forcefully undermines the efforts to resolve border disputes by China and Bhutan through diplomatic and political means.

China and Bhutan started their border negotiations in the 1980s, and have held 24 rounds of talks so far. In August 2016, after the 24th round, Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Liu Zhenmin declared that the two countries’ border negotiations had made great progress in recent years. Despite the progress, the prospects for an agreement remain weak because Bhutan remains so close to India. As for the “Doklam dispute,” China’s position is very clear: China must defend its rights specified in the 1890 treaty and strengthens its effective jurisdiction over the Doklam area. This position evidences China’s respect for the treaty as well as international law. However, because Bhutan has some disagreement on the 1890 treaty, China is willing to negotiate a “packaged solution” through peaceful means.

India often claims it “works closely with Bhutan to prevent damage to both nations’ interests.” But illegally encroaching into China’s territory “for Bhutan” neither aligns with the friendly consultations conducted between China and Bhutan, nor protects Bhutan’s national interests. India’s move is Modi administration taking advantage of Bhutan to protect its own interests. The event has exposed how India is manipulating Bhutan’s internal and external affairs. The “friendly treaty” signed in 1949 between India and Bhutan stipulated that “Bhutan agrees to accept the guidance of the Indian government in diplomatic relations.” Not until 2007 were changes made to the imbalanced treaty, the most important of which was changing the word “guidance” into “close cooperation.” But that change seems to be only superficial, and in practice Bhutan seems to be a protective patron of India.

The 24 rounds of negotiations over the past 33 years have led to many consensuses between China and Bhutan concerning border area. Yet, Bhutan has never formally established diplomatic relations with China because of Indian manipulation. Of the 14 nations sharing a border with China, only Bhutan lacks formal diplomatic ties to China. And Bhutan is one of only two countries with an ongoing border issue with China. The other country is of course India. Using Bhutan as a pawn is failing to capitalize on its strategic advantages due to its geographic position directly between the world’s two largest emerging economies. Bhutan could be enjoying the fruits of development, but it remains one of the Least Developed Countries in the world.

Third, India is ignorant about the overall situation of China-India relations. Hard-earned stability in bilateral relations requires efforts to sustain. Although China and India are confronted by challenges of developmental competition, clashing strategies, disputes over territorial sovereignty and problems left by history, the countries share enough mutual dependence in geopolitics, complementary positions in development, mutual reliance in national strategies, and cultural connection to develop a rich and mutually beneficial relationship. For the two emerging economies with huge populations and long histories, ensuring that both governments optimally benefit their peoples during development is the primary goal of bilateral cooperation. Chinese President Xi Jinping stressed that China and India, as the two largest developing countries in the world, should properly manage and handle disagreements and sensitive issues when he met Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi on June 9, 2017, in Astana, Kazakhstan. Modi agreed and noted that the two countries should explore potential for cooperation, strengthen communication and coordination in international affairs and respect each other’s core interests and major concerns. The standoff in Doklam, however, unfolded and was clearly caused by the Indian government when those words were still fresh. New Delhi unilaterally opted to forgo “properly” handling the disagreement in favor of triggering a larger dispute. The incident will leave a deep and prolonged strain on China-India relations. Considering the current development status and bilateral relations of the two countries, the event will likely destabilize regional and global cooperation between China and India, considering how aggressively the Modi government addresses disagreements. Furthermore, India will endure a deteriorating image in the eyes of Chinese people and less favorable China policy toward India.

India, a civilization of over five millennia, is the second most populated country in the world, following only China. Governed by a multi-party system since 1952, the politically-mature country would not make such poor decisions if common sense was a guiding principle of the current government. The standoff persists today and casts a dark shadow over the entire region.

The incident was born with Indian strategists, particularly Modi’s policy consultants, who have shown an obsession with absolute security that has driven the Indian government to treat perceived security threats as real, even at the cost of disturbing the domestic and foreign affairs of other countries including Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bhutan. The driving motive for the Modi government to cause this standoff is Indian strategists’ concern that the Siliguri Corridor, India’s strategic hub, would be threatened if China builds roads to Mount Gimpochi. These analysts are intimidating themselves, however, and creating an illusory new cold war to keep themselves relevant. Such concerns hardly make sense considering India’s strong military forces positioned on both sides of the corridor all the way from Doklam. It’s difficult to argue that India’s sabotage of its neighbor’s legitimate infrastructure project in the border area in the name of “absolute security” benefits anyone.

In fact, “absolute security” far transcends borders if the concept is treated like zero-sum game in which one country’s security becomes a threat to its neighbor. It will only lead to an arms race. As the standoff in Doklam continues, China is seeing that its forces on the border are far weaker than those of India, so China is looking harder at catching up with India through its ongoing military reform and modernizing its defense facilities near the boundaries to enable the country to better curb India’s impulses to conduct standoffs and end them before they start. India should be seeking sustainable security rather than absolute security, which can only be attained through win-win cooperation.

Why is India, especially the Modi administration, so obsessed with absolute security? Three key factors are influencing the government’s actions:

First, India’s strategic thinking is suffering from inertia. India considers itself a natural inheritor of the British Empire’s colonial heritage. One legacy the British passed on to the India’s ruling elites is the Buffer Zone theory, which was developed during 200 years of colonial dominance that started with the Battle of Plassey in 1757 and ending with British evacuation from the Indian subcontinent in 1947. According to the theory, Tibet should be the buffer zone between China and India, and the Himalayas the natural barrier. Therefore, the Nehru administration (1947-1964) strongly opposed the Chinese central government’s peaceful liberation of Tibet. Indian elites would have preferred that Tibet keep its half-independent status forever, and India signed friendship treaties with Nepal, Bhutan and Sikkim soon after it won independence to manipulate the security and diplomatic policies of those small states along the Himalayas. Consequently, New Delhi doesn’t want to see the construction and operation of the China-Nepal Railway and the establishment of normal diplomatic ties between China and Bhutan.

In the Doklam standoff, India wants to make Doklam a small buffer zone by preventing China from constructing any frontier facilities there so that India has absolute unilateral defense advantages for the long term. However, poor and backward Bhutan, Nepal and even the northern and northeastern part of India are the biggest victims of the Buffer Zone theory and practices, which are supported only by the Indian ruling class and strategic think-tanks.

Second, the situation is worsened by the Modi administration’s overwhelming confidence. Since Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi took office in 2014, many achievements have been made in both the domestic and foreign affairs of India. In the foreign affairs, the India-U.S. security partnership has made many big strides towards the bonds of alliance, and the India-Japan security agreement has continually reached new levels. Trilateral dialogue between the U.S., Japan and India has become increasingly concrete and high-reaching. The scale of the Malabar naval exercise involving all three countries has grown and could soon involve Australia too. The India-Africa Forum Summit (IAFS) and Forum for India-Pacific Islands Cooperation (FIPIC) are attracting more and more participation.

In this context, it’s no surprise that India’s Minister of State for External Affairs Vijay Kumar Singh has declared with great confidence that the majority of countries around the world support India on the Doklam standoff. In domestic affairs, Modi launched the Goods and Services Tax (GST), India’s biggest tax reform since independence, and established the first unified market in history. Modi’s strong cash ban enabled leap-frog development of domestic mobile payments. And largely thanks to Modi’s whirlwind influence, his Bharatiya Janata Party won a landslide victory in the politically crucial northern state of Uttar Pradesh, further consolidating the party’s dominance of India politics. In each of the past three years of Modi administration, India has had an impressive macroeconomic performance. Not only has its GDP growth rate surpassed China, but it also became the top market for international greenfield investors. Surprising successes of past aggressive polices further stimulated even bolder and more aggressively impulsive moves from the Modi administration. The Doklam standoff is just one of them.

Third, the Modi administration has deepened hostility toward China. The election victories of Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party ended the ruling status of the coalition government of the past 30 years and greatly enhanced the government’s decision-making capacity, which once produced huge hopes for great development between China and India.

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang scheduled his first state visit to India two months after he took office in 2013. The Chinese government even broke the tradition of ensuring that the Premier’s South-Asian trip includes both India and Pakistan. And Premier Li called Modi to congratulate him soon after Modi took office. On many occasions, Chinese President Xi Jinping has proposed discussions with Modi on the possibility of aligning the Belt and Road Initiative with India’s Monsoon Plan, Spice Route and Cotton Route.

In general, the Chinese government’s diplomatic policies towards India are intended to broaden consensus to reduce the impact of differences between the two countries on bilateral relations. However, China’s good intentions are often frustrated by India’s negative diplomatic responses. Because the Modi administration doesn’t believe China and India can develop bilateral ties and conduct strategic cooperation without first settling the disputes, especially on the border issue. Furthermore, they misconstrue Chinese diplomatic reactions as intending to check the rise of India. The administration treats China as its arch rival, which has inspired it to embrace various security cooperation strategies offered by the U.S. and its allies to contain China and curb its influence.

The Modi administration’s resulting hostility towards China is putting China-India relations on thin ice, and the dynamic could quickly shift from cooperative and competitive to adversarial. However, the more adversarial China-India relations become, the easier it would be for India to take extreme precautions against China. The Doklam standoff is just one example.

So, how the Doklam standoff issue is ultimately solved will likely present a possible turning point for the Chinese government’s South Asian policy.

The author is the director of the Institute of South Asian, Southeast Asian and Oceanian Studies of China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations.