India Wants to Learn from the Rise of China

“India’s rise” is a hot topic in academic circle now, especially after a series of announcements made by the Indian government about GDP growth surpassing that of China. Many American, European and Indian media are cheering excitedly x “India has become the world’s engine of growth, surpassing China,” “India is the dawn after the world economic slump,” and so on. However, there are also voices of suspicion that India’s economic growth is “fudged.” After all, what is the truth behind “India’s rise”?

On June 13 and 14, 2016,Mumbai hosted the Group of Twenty (G20) Think Tank Summit (T20) and “Gateway of India Dialogue” which attracted several hundred think tanks and elite figures in the field of economic policy from more than 10 countries like China, India, the United States, Canada, Japan and the Republic of Korea. I attended by invitation. Through exchanges and debates in the academic hall, chats on the street, and some surveys, I feel it necessary to set aside the economic data and tell the Chinese readers about the real situation of India’s development.

Slums: Scars of India’s Development

People who arrive in Mumbai for the first time all praise the design and streamlined appearance of Terminal 2 of the Mumbai International Airport. The huge terminal building was completed in January 2014, and can handle 40 million passengers every year. It is very similar to Terminal 3 of Shenzhen Airport which was put into use two years earlier and has won an international space design award. Once out of the Mumbai Customs, the first word came into my mind was the “rise of India.”

Chhatrapati Shivaji International Airport in Mumbai is the largest and most primary aviation hub of India, with annual passenger traffic of 4,000.

However, once out of the airport, what I saw were dilapidated single-story houses and garbages on both sides of the bumpy expressway. This reminds me of what my Indian colleague had said. Akshay Mathur, director of the geo-economic studies department of the Indian think tank – Gateway House, once told me: “The rapid growth of India’s GDP seems pointless now. Look at the millions of people still living in slums. Confronted with the wide disparity between the rich and the poor, a GDP growth of 7 or 8 percent is simply negligible. The scholars must be independent-minded when thinking about the rise of India.”

Indeed, in Malabar Hill – Mumbai’s richest area, soaring skyscrapers, magnificent hotels and restaurants, and a crowd in trim Western attire – conditions can be comparable to that of central Hong Kong. But, a few kilometers away are slums spread all over, which are wretched, overcrowded and survive amidst poor conditions. Dharavi in Mumbai is Asia’s largest slum, where live millions from the lowest rung of the society.

Dharavi, located in central Mumbai, is the largest one among Mumbai’s 2000 slums. Within an area of just 1.75 square kilometers, the residents there account over one million.

Nearly 200 million people live in slums, which are the scars of India’s development. However, the private ownership of property, premature political democratization, and the caste system – which though abolished long before is still of crucial importance in real life – are the three critical factors that leave India with almost no possibility of completely healing the “scars.” In close proximity to these scars are the problems of crimes, prostitution, drug abuse, pollution, corruption, increasing illiteracy and the accompanying anarchy in the slums.

In Mumbai, I mentioned: “Twenty years ago, many Chinese cities had slum-like shanty towns, but now the transformation is basically completed. In the last 30 years, China has lifted 600 million people out of poverty. In this regard, India might as well learn from China’s experience in poverty reduction.” The nearly 300 personage from all walks of life in India present at the venue listened very carefully, some applauding. Some Indian scholars also consulted me outside the hall about the experience of China’s economic development zones and relevant issues.

The Absence of China’s Experience

India’s elite is paying increasing attention to China. Mumbai T20 think tank meeting is a warm-up for this year’s G20 summit in China, and an international meeting for communication. One of the hot topics during this meeting was, after Germany in 2017, who would host this “premier forum for global economic governance?”

The most likely candidate is Argentina, because the G20 summit has never been held in South America. But India is also very interested, and hopes to bid for 2018 or 2019 G20 summit. When I expressed my personal support for India’s bid at the T20 meeting, many Indian scholars were very excited, and expressed their strong wish to “strengthening communication with China.” An Indian scholar who makes research in global economic governance revealed that India, unlike China, has never hosted a global congress. In recent years, China has organized the Olympic Games and World Expo one after another. And, this year’s G20 summit in Hangzhou is seen as the “coronation ceremony” of China formally becoming a global power.

The Broken Bridge on the West Lake, Hangzhou, China. On September 4 to 5, 2016, the 11th G20 Summit will be held in Hangzhou, under the theme of "Toward an Innovative, Invigorated, Interconnected and Inclusive World Economy".

Indian people have long been watching the West attentively, admiring greatly the developed countries like the U.S., Europe and Japan. Now, Indians have begun to envy China’s global influence and its rising power of being able to have its say.

At the Gateway of India Dialogue, India’s Minister of State for External Affairs, V. K. Singh, in his keynote address, repeatedly stressed the importance of “Look East,” emphasizing the mutual benefits between India and its neighbors. The organizers specially wrote to me three days before the Dialogue, asking if I was willing to deliver a keynote speech.

June 14, 2016, Mumbai: Panel discussions during the Gateway of Indian Dialogue.

They revealed that they rarely have, before this, invited Chinese scholars to the forum. Actually, there are many Japanese guests, because the Japanese have done a lot of public diplomacy with India, but India now feels it necessary to listen to the voice of Chinese people. Sure enough, I was the only Chinese scholar who publicly spoke at the forum. In the group dialogue there were two Japanese who shared the stage: Seiji Takagi, Bureau Chief of Japan’s Sankei Provincial Trade Policy Division, and Nishimura Hidetoshi, Director of Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia.

After nearly one and half hours of conversation, many Indian scholars surrounded me and asked for my business card. Professor Daswani of the Mumbai Law College said that in the past India’s views on trade and the international system were heavily influenced by Japan, Europe and the US, and he had never heard such novel viewpoints from a Chinese scholar.

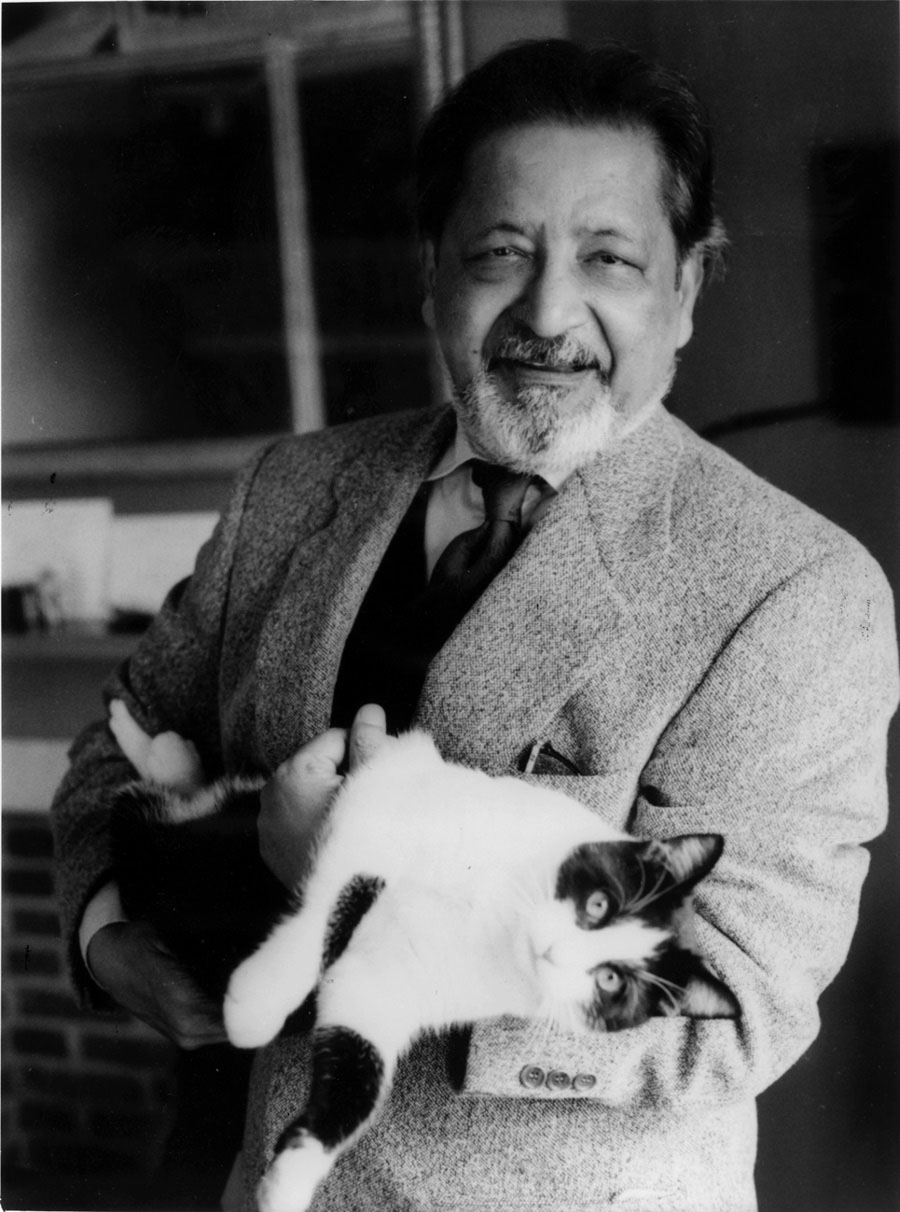

Such remarks made me to remind the observation of the Indian-origin writer, Nobel laureate V·S·Naipaul in his masterpiece An Area of Darkness: “The Indians are unwilling to face the predicament of their own country… they are forced to shrink back into the Western fantasy.” In reflection on India’s national rise, there is the lack of knowledge modules from China. Once the Indians contact with them, the shock in their inner world would be great.

V.S. Naipaul, a Nobel literature laureate, dissected a variety of Indian culture and social issues in his Indian Trilogy.

Kapil Kapoor, executive vice president of the African Development Bank, told me: “Now the international opinion towards the rise of India may be somewhat optimistic as compared to the rise of China.” Kramer, the President of the German Institute of Ecology, who had been to China many times, said: “China is indeed many years ahead of India in all aspects. For example, China’s executive power, and the unity between central and local governments are beyond comparison with India’s.”

Shared Rise of Over 20 Million People in China and India

Although India’s total GDP is only one fifth of China’s, we have to admit that India’s economic growth in recent years is indeed eye-catching. Prime Minister Modi’s drastic reforms are also catching everybody’s attention. As far as innovation in the fields of software industry, film industry, finance and IT is concerned, India in no way is inferior to China, and in some areas is even stronger.

In India, I could easily feel the sense of national pride and confidence in the country among the local people. A taxi driver told me: “I would like to go to China. China is richer than India, but India will get better and better.” A slum dweller belonging to the Hindu faith said: “Prime Minister Modi has let us see the hope, we also have dreams – as depicted in the movie Slumdog Millionaire.” In the slum, so many men were smilingly working, and women, no matter how poor, were all dressed in bright colors, making it easy for me to perceive the optimism of the Indian people.

In addition to the Indian media’s focus on the country’s economic growth, the “Rise of India” theory has acquired a functional logic of the American think tanks that are supporting India to suppress China. And, in recent years, some of these foreign scholars, who don’t speak very highly of the rise of China or don’t much approve of China’s political system, often contrast China’s rise with the rise of India. To some extent, it is suspected that they are concocting “China-India competition” or inciting China-India conflict.

Even more important are the arguments trying to make use of the “Rise of India” theory to negate the basic fact that China can achieve its rise without walking on the path of Western-style democracy and without China being lured to learn from India.

Faced with the hyped-up “India’s rise”, Chinese society should be more confident. In my opinion, viewed from the angle of the rise of a nation changing the fate of the people and raising the role of a civilization, the significance of China’s rise is much greater than India’s rise. The former is a revolutionary development paradigm, an intellectual revolution at the philosophical level, while the latter is still by far a repetition of the Western paradigm, just a new experiment in national development from an economic perspective.

Though there is no way India can get rid of some of its “scars” in the process of development, during my exchanges with the Indian scholars, I could feel that the Indian economy would continue its upward trend in the future. Readers in China should fully recognize that the rise of India is more beneficial than harmful to China. The average age of Indians is about ten years younger than that of Chinese; the domestic infrastructure construction and consumer markets are huge; and, these conditions could provide Chinese firms with a lot of opportunities to expand over there. In comparison, China-India mutual exchanges are still very limited. In 2015, the number of two-way exchanges between China and India was a mere 0.9 million people, approximately one sixth of Sino-US exchanges.

The “super tonnage” rise experienced by the more than 2.5 billion people in China and India is unprecedented in human history. Promoting the rise of India will also benefit China in its more sustainable development.

The author is executive dean of Chongyang Institute of Financial Studies(CIFS) at Renmin University of China, studied at Lanzhou University, Hong Kong Baptist University, the Jonhs Hopkins University, Nanjing University Center for Chinese and American Studies, and Peking University. He was a commentator and member of the Editorial Committee of Global Times. In 2011, he won the China News Awards. At the end of 2012, he participated in setting up the CIFS.