India’s Slow Steps into 2017

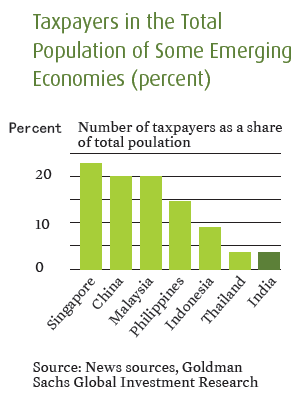

Despite the positioning of the ‘development agenda’ as a flagship goal of the current Indian government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, a web of complicated rules for taxation and compliance procedures has resulted in India consistently ranking as one of the toughest nations in which to start a business.

India’s massive young population and fast-growing middle class are providing a growing market for foreign companies hoping to expand their operations. However, the persistent red tape has been a serious deterrent.

Entrepreneurs and industry leaders have long complained that India’s complex and outdated labor laws and the wide discretionary powers of labor inspectors have been major impediments for expanding Indian manufacturing and exports, despite the abundant supply of affordable labor. Indian businessmen are often subjected to heavy-handed, arbitrary or corrupt enforcement of regulations and bureaucratic scrutiny, which is largely referred to as “inspector raj”.

China and other Asian countries have rapidly strengthened labor-intensive industries and export-friendly tax policies, but Indian manufacturing has remained stagnant at roughly 18 percent of national economic output. India consistently ranks on the wrong end of the World Bank’s listing for “ease of doing business.”

The current government, led by the right-wing Bhartiya Janta Party, won an overwhelming, historic majority in 2014 on a platform of development and good governance, riding a wave of popularity surrounding the former Chief Minister of Gujarat and current Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Widely considered an investor-friendly official, Modi facilitated a booming economy and lured major foreign and Indian companies to invest in his coastal state, which gained fame for its entrepreneurial spirit and comparative ease of doing business.

February 7, 2011, Old Delhi: A man selling sweets pushes his cart through the streets in the Main Bazaar. [CFP]

Since Modi became Prime Minister, his government has introduced a series of reforms to eliminate arcane rules and simplify procedures.

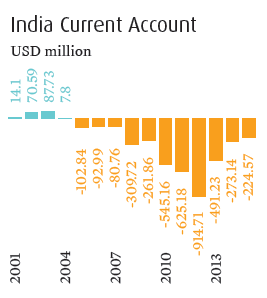

On a positive note, in 2015, India became one of the world’s fastest-growing major economies, with a gross domestic product growth of 7.6 percent. Slumping oil prices have helped curtail inflation and improve corporate margins, and a rebound in farm output has helped strengthen current and fiscal accounts.

Modi’s opening of sectors such as railways and defense helped draw record foreign direct investment in 2015—during a period when investors were fleeing emerging markets. That inflow has helped lift foreign exchange reserves by US$47 billion since the end of March 2014 to US$350 billion at the end of December, 2016.

Modi also aims to transform the nation into a global manufacturing hub with his “Make in India” initiative. The program has resonated with global leaders and attracted more than US$400 billion in overseas investment commitments. If all the deals hold up, they would account for more incoming investment than the country has seen in over a decade. The government hopes to create 100 million new factory jobs by 2022 and lift manufacturing’s share of the economy up to 25 percent by 2022 from about 18 percent when Modi took office.

Many of the initiatives meant to make business easier are significant individually. Eliminating forms, facilitating certain processes online, setting deadlines for approvals, allowing self or third-party certification, and simplifying and illuminating processes have made business much easier. The Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, which went into effect in 2016, fixes many problems with the Arbitration and Conciliation Act of 1996, including long, drawn-out proceedings resembling court cases. The new law facilitates speedy resolution of disputes. For infrastructure companies dogged by arbitration cases, the move has lifted a huge burden.

Uniform Tax System

Described as the biggest reform aiming to simplify the colossally complex Indian tax system, the Goods and Services tax, known as “GST”, has been languishing in the Indian parliamentary system for over a decade. The Modi government plans to replace local taxation with a uniform federal tax system for the entire nation, with local deficits offset by federal funds. Once fully implemented, it would increase the ease of doing business in India in leaps and bounds. The GST is also expected to introduce a simple, efficient and uniform indirect tax structure to India via a comprehensive tax levied on all goods and services together.

The GST plan is intended to eliminate many shortcomings of the existing indirect tax structure. The GST Council is finalizing brackets after the Centre and State agreed to a 4-bracket structured at 5 percent, 12 percent, 8 percent and 28 percent.

The tax will be implemented in stages beginning in the fiscal year that starts April 1, 2017.

Although analysts and industry leaders are not ruling out initial hiccups while moving towards the ‘One Nation, One Market’ concept under the GST regime, Indian industry is set to benefit from the new tax system in a big way over the years.

A year after the GST goes into effect, it will help to more efficiently allocate resources, eliminate supply disruptions, put inflation in check, buoy tax revenues and improve compliance, leading to a two-percentage-point increase in economic growth.

The manufacturing sector in particular is expected to be a big beneficiary of the GST when the economic system becomes more competitive. Because the GST will be aligned with an information technology platform, the tax payment system will also be streamlined. It will certainly be a tough task to roll out the GST in a nation as vast and complex as India, but the new tax system is expected to eventually become standardized and workable after fine-tuning and alignments across various states.

Currency Crackdown and Impact

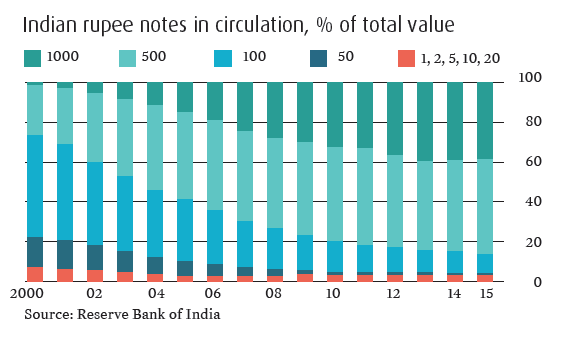

Another major step was the Indian government’s sudden move to withdraw larger banknotes from circulation to combat corruption. The demonetization sent shockwaves through the Indian economy.

The elimination of 500 and 1,000 rupee bills, which constituted over 80 percent of liquid cash in the economy, was intended to flush out money hidden from the tax collectors. However, it has led to confusion and anger among citizens throughout the country, who are having a harder time accessing their money. The decision caused a rush to banks, where thousands queued up to exchange old notes for new ones. ATMs closed suddenly to be recalibrated to accommodate the new currency.

With money becoming scarce and cash being returned to the banking system, less organized institutions such as small and medium sized businesses endured the worst troubles. As the old 500 and 1,000 rupee notes are reintroduced to the banking sector, deposits are likely to swell, and lending and deposit rates could fall by year-end. Government bonds have already seen an impressive rally.

Most of India’s rural economy runs on cash, so the government has been taking active steps to move the system to the digital world, where a virtual paper trail makes tax evasion much riskier.

Shortly after winning a majority in the 2014 elections, the BJP government announced that it would launch a scheme called the Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana, to improve financial accountability. The program involves massive tasks such as opening empty bank accounts for the entire Indian population and issuing debit cards, enhancing overdraft protection and providing insurance coverage. The program is intended to introduce poorer citizens to banking facilities and empower them by encouraging savings and easing loan delivery and direct cash transfers.

According to estimates, a record 160 million bank accounts were opened, with a volume that set a Guinness World Record. However, analysis showed that the vast majority of bank accounts stayed empty and unused, creating a huge strain on banks. Simultaneously, the government launched an income declaration program that encouraged people to report previously undisclosed income or assets by offering immunity in exchange for a simple 45 percent tax on the assets. After the currency move, however, the new bank accounts started seeing a massive influx of funds alongside many allegations of impropriety. Law enforcement agencies have been closely monitoring activity for large, sudden deposits.

However beneficial the move will prove in the long run, especially if accompanied by other steps to curb dirty money, the black market’s admittance to the books will cause an uptick in terror financing and major tax collection, resulting in intense short-term pain. Moreover, the government’s critics argue that the administration may have underestimated the economic costs of removing cash—even temporarily —from a largely cash-based economy. They paint an alarming portrait via tales of grief, dislocation and uncertainty, with stories of disrupted food and medical supplies and large labor-intensive sectors of the economy becoming effectively paralyzed for months.

Critics, who believe that most illegally acquired money is stashed abroad or converted into assets such as real estate and gold, have also questioned the ultimate effectiveness of the scheme. They argue that the policy largely only hurts the vulnerable, small businessmen and traders. Opposition parties argue that implementation was poorly planned, causing severe hardship for a vast section of the public, and that the actual economics of the scheme do not add up. During his 2014 election campaign, Modi promised to bring to light billions of dollars that he claimed were illicit funds held in overseas bank accounts.

Economists estimate that growth in India could fall by 0.7 to a full percentage point in the next year, with the maximum impact on the next two quarters after such a large contraction in effective money supply.

While the Indian government has embarked on some big reforms, not all of Modi’s policies have been aimed at courting foreign investors. In a bid to boost the domestic steel sector, which has slumped, the Commerce Ministry recommended a provisional anti-dumping duty of up to US$557 per ton on sheet and plate imports from six countries: China, Japan, South Korea, Russia, Brazil and Indonesia.

On the domestic front, some other key aspects of governmental reform have also come up short. The BJP government has been unable to amend the land acquisition bill, which has caused nightmares for many businesses trying to acquire land in India. The government has also preserved mechanisms to impose taxes retroactively, causing headaches for foreign investors, and shelved efforts to make labor laws more flexible.

Furthermore, exports remain weak, and bad loans rose to a 14-year high by the end of September, presenting a potential drag on growth, while corporate profits bottleneck economic expansion. Despite consistent steps by the Indian government, the country continues to rank near the bottom in ease of doing business.

Trump Factor and Brexit

Global uncertainty is also likely to affect the Indian economy. The globalization trend is currently facing a major crisis. Like a thunderous echo of the Brexit moment, Donald Trump was elected 45th President of the United States after campaigning against globalization. India’s IT exports to the U.S. are valued at US$80 billion and account for over two-thirds of all of the country’s IT exports. If Trump acts on his H1-B visa promise, it could be disastrous for India’s tech sector. About 1.7 million such visas are currently issued each year. A cut on U.S. corporate taxes from 35 percent to 15 percent could lead to an American corporate exodus from India, especially in sectors such as automobiles, IT, computers, insurance and chemicals.

While India may be poised for long-term economic growth, it has swallowed a bitter pill meant to treat the symptoms of a fragile economic recovery and could see a resulting short-term slump as the impact of some of the radical legislative changes and reforms settles in. The Indian economy is expected to slow in the first half of 2017 but pick up later in the year, as the country adjusts to some of these changes.

The author is an Indian freelance business journalist. She has covered business and finance for the Hindu Business Line, reporting on topics such as banking, insurance, education, and healthcare. Currently, she also works as a communications consultant for Bajaj Allianz General Insurance.