Infrastructure: Little Things Make It Big

Infrastructure is a long, boring word. By the time you’ve finished saying it, the audience has yawned and gone to sleep. Yet life could be impossible without infrastructure. The everyday essentials for living – water, food, shelter, electricity, petrol, roads, bridges, schools, colleges, hospitals, trains, buses, planes, phones, telecom, internet and so much else – add up to infrastructure. It is almost as difficult to describe or define as civilization.

Perhaps, it is not a coincidence that, through artefacts, when civilizations are re-imagined and re-constructed, they are marveled at for the ‘infrastructure’ they had in their time. Infrastructure is taken for so much granted. So much so, that few spare a thought to how it makes life livable, comfortable and convenient. Only when it is not there, does one realize how essential and invaluable infrastructure is for living. Infrastructure is at the core of development. In the absence of infrastructure, development is not attainable. Doubtless, ‘development’ itself is a controversial term.

Workers of a Chinese ultra-high voltage engineering team install power towers. by Zheng Zuzhi

Development means different things to different people. Thanks to free flowing information and images in this age of media and rising aspirations in the southern nations, the word has gained worldwide currency. In spite of its loaded, conflicting meanings, ‘development’ has acquired an implied clarity of meaning across the world, among the poor as well as the prosperous, the deprived and the ‘developed’. The word has acquired universal acceptance and awe across countries, cultures, religions, ideologies and political systems.

In his seminal work, The History of Development: From Western Origins to Global Faith, Gilbert Rist defines development as: “A set of practices, sometimes appearing to conflict with one another, which require – for the reproduction of society – the general transformation and destruction of national environment and of social relations. Its aim is to increase the production of commodities (goods and services) geared, by way of exchange, to effective demand.”

The 28-kilometer-long Hangzhou Bay Bridge, which began operation in 2008, is the second longest cross-sea bridge in the world.

In the course of my early travels to the West, I understood that ‘development’ is the difference between the ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ countries. As much as the skyline and city lights of London, Paris, Berlin and New York, what amazed me was the uninterrupted supply of electricity and water, various modes of efficient and rapid public transport, telecommunication and the many structures of convenience that made for a better quality of life and higher standard of living. These, in turn, made for better health, higher efficiency, more productive work and improved economical functioning.

That exposure imprinted in my mind that development is just another word for infrastructure, which I then translated as ‘structures of convenience for living’. Equally etched in my mind was that infrastructure – a word I never liked to use – was something for ‘Them’ in the advanced industrialized countries and not for ‘Us’ in the developing southern nations. That was until I visited China.

China boasts a well-developed high-speed railway network.

Travelling to Beijing, first with Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in 2008 when he went for his economic summit with Premier Wen Jiabao and, thereafter, on work for long and short spells, opened my eyes to how much of the ‘developed’ can be achieved as development in a ‘developing’ country.

Wind turbines in China.

After a few long visits and short stays in Europe, I concluded that these small countries with populations so much smaller than India and China, could afford the infrastructure and the development flowing from it. Without going too far back in history, it can be said that Europe could afford a better life based on appropriation of the wealth, resources and products of the colonies over a long period. After World War II, there was the Marshall Plan, under which the US pumped in huge resources. The Cold War may have been a bad time, but it was also a good time for Europe with its West and East being developed and bankrolled by their respective superpower-patrons. NATO gave West Europe an advantage over East Europe, although the East lagged behind and remained, relatively, backward. With so many governments for a population of about 600 million in 50 states (excluding Russia), great infrastructure, high employment, good quality of life and higher standard of living was no big deal.

India has planned to increase investment of US$ 137 billion in constructing its heavy-haul railway network within five years since 2015.

In contrast, for the nearly three billion people of India and China taken together, there are only two national governments. Both countries have been victims of colonialism and imperialism and were blocked for long from access to technology and the goodies of the industrialized West that would have hastened their development. Given this background, the political stability along with economic, social and human development achieved by India and China, since 1947 and 1949 respectively, is indeed impressive.

China’s achievements are more impressive than that of India despite the different political systems of these two countries. What struck me most during my first visit in January 2008 was China’s stupendous infrastructure, and the breakneck speed at which it was being developed in the months leading to the Olympic Games scheduled to be held later that year in Beijing. In the years since then, during visits to the provinces and work stints in Beijing, I noticed that the development of infrastructure – housing, business districts, commercial buildings, malls, markets, metro lines, ring roads, bridges, flyovers, power stations, schools, universities and new hubs of technology, transport, telecom, energy, transshipment, railways – continues unabated. The momentum of development remains much as it was during the countdown to the Olympics.

In 2012, Shanghai Citi-Raise Construction Group won the bid for the New Delhi subway project.

Seeing this in China convinced me that infrastructure development is achievable even for countries with a large population; and, that scale and size need not be a deterrent. On the contrary, in a larger country, the cost and benefits can be spread over a larger area and population. I now believe that the high level of development once seen only in Europe and the US (besides parts of Asia like Japan, Singapore and Malaysia) need no longer be a distant dream for India and other developing countries in the region.

China’s transformation in a short time is awesome in scale and sweep. More than 700 million people have been lifted out of poverty in the last three decades. Thirty years of turbo-charged economic growth has changed for all time the semi-feudal, semi-colonial condition of a people who were dirt poor. Once condemned as irrelevant, isolated and backward China has emerged as a global power that is at once both courted and feared. Its rise as the world’s second largest economy, stable and prosperous enough to feed 1.3 billion people and hold its own against any and all is without precedent in history.

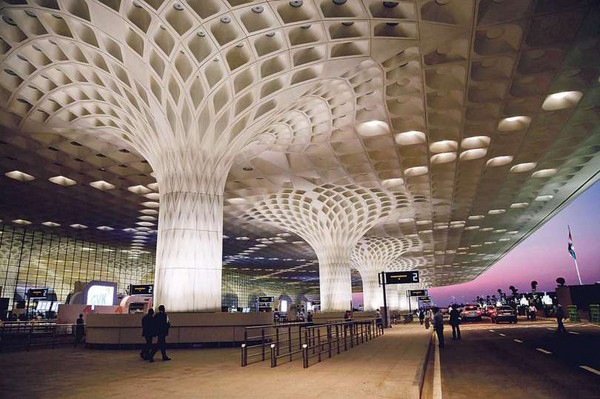

The modern Mumbai International Airport is the most important aviation hub of India.

Not once during my long periods of stay in China have I faced water shortage or power outage. At no time did I experience a single minute’s cut in electricity or water supply. In China, everything – power and water supplies, infrastructure, systems and services – works and, where required, round the clock for 365 days in a year. It is, therefore, no surprise that today, much like the US, ‘the business of China is business’.

India has much to be proud of. In many spheres, its achievements surpass or compare favourably with that of the West. Yet, India’s potential remains unrealized because it is weighed down by poverty, unemployment and poor infrastructure which, in turn, retard development and growth with equity and justice.

Regardless of the many social, political and cultural differences between the Asian giants, China’s experience, poverty alleviation measures and development trajectory are of immense relevance to India. Therefore, China can play an important role in India’s development agenda. The ‘Make in India’ program is a leaf taken out of China’s experience for development of the manufacturing industry as a prerequisite for the millions of jobs that have to be created. Manufacturing and infrastructure development are inextricably linked. Both go together, and it is together that infrastructure and manufacturing can generate employment, boost productivity, drive growth and make the developmental leap out of poverty and inequality.

The staff of Shanghai Citi-Raise Construction Group working at a subway construction site in New Delhi, India.

India has the advantage of being able to choose what is appropriate from the Chinese experience. China has much to profit from partnering India. It would be serving its own interest by exporting infrastructure projects, setting up manufacturing units and finding a new market of over a billion for its companies, projects, products and services. The outcome, to use a phrase the Chinese love, would be ‘win-win’ for both.

The author is Senior Consultant and Editor of China-India Dialogue, CIPG.

This article is exclusive to China-India Dialogue. Feel free to share this article. To reprint this article, please contact us for permission.