Make in India vs. Made in China

After Prime Minister Narendra Modi took office in 2014, the government of India initiated the “Make in India” program in a bid to relieve employment pressure, increase the ratio of manufacturing in its national economy, bolster economic growth, diversify exports, and improve Indian products’ international competitiveness.

To date, the “Make in India” program has received positive response from multinational companies investing in India, including Mentor, Samsung, and General Motors.

Early this year, Chinese electronics giant Foxconn announced it would establish the world’s largest OEM manufacturing park in Andhra Pradesh, India. Whether “Make in India” will surpass “Made in China” has become a hot topic.

Challenging “Made in China” with “Make in India”

India’s manufacturing has constantly grown in recent years. According to statistics released by the World Bank, the incremental value of India’s manufacturing sector amounted to US$ 344.563 billion in 2015, accounting for only 10.06 percent of that of China, which stayed at nearly US$ 3.25 trillion.

The World Bank statistics also show that the incremental value of China’s manufacturing industry made up 33 percent of its GDP in 2015, while the figure was only 13 percent for India, much lower than the goal of 25 percent set by Modi in a speech he made early this year. This implies that manufacturing plays a much more important role in China’s national economy than in that of India.

Currently, China occupies a position in the middle of the global manufacturing chain, while India is still at the low end. In this context, the government of India formulated the “Make in India” program, hoping to catch up with and even surpass “Made in China” through a series of incentive measures.

Advantages of “Make in India”

In order to attract domestic and foreign investors, especially multinational manufacturing giants, to invest in India, the Modi administration has conducted economic reforms through measures such as implementing tax reduction and exemption, improving infrastructure, revising the Labor Act, reducing operation costs, providing enterprises with allowances, setting up special economic zones, protecting domestic manufacturers, and prompting exports.

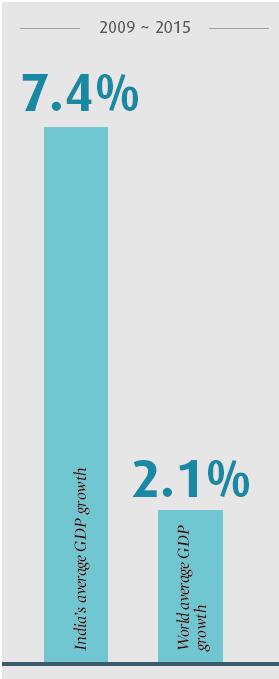

As the world’s second largest developing country, India is one of the fastest-growing economies and has obvious advantages in expanding its manufacturing industry.

As the world’s second largest developing country, India is one of the fastest-growing economies and has obvious advantages in expanding its manufacturing industry.

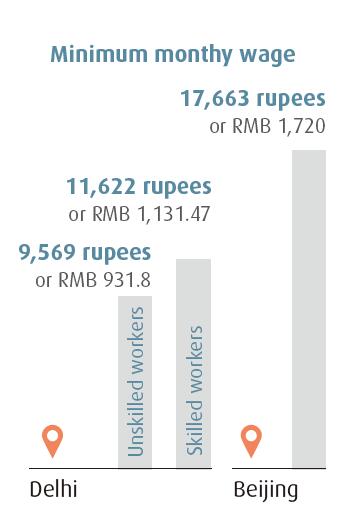

First, India’s abundant, cheap labor increases the cost advantage of “Make in India.” According to World Development Indicators, people aged between 18 and 64 accounted for 66 percent of India’s total population in 2015 (the figure was 73 percent in China). It is estimated that India’s labor population will increase by 110 million in the next 10 years, while the number of China’s laborers between 20 and 24 will decrease by 30 percent.

Moreover, India has long been among countries with the lowest labor costs.

Considering India’s abundant labor force and comparatively low labor costs, those labor-intensive industries with low technological thresholds, such as textile, clothing, and shoes manufacturing, will have a strong potential for growth in India. Such a situation is helpful for India to develop an export-oriented economy.

Second, the considerable purchasing power of Indians arising from the country’s impressive growth has created a favorable economic environment for promoting the “Make in India” program.

A recent nationwide survey in India indicates that the country has 69.11 million middle-income households. Assuming that each household has four members, India’s middle-income population is expected to amount to 280 million. “India’s consumer goods market is conservatively estimated to double and reach US$3 trillion by 2030,” predicts renowned capital economist Shah.

Third, India’s comparatively complete industrial system has laid a solid foundation for the fulfillment of the “Make in India” program. When ruled by the British, India had textile and mining as its mainstay industries. After Independence, the leadership headed by Jawaharlal Nehru made up its mind to build India into a great industrial power and set industrialization as a major objective for its economic development. Through more than five decades of effort, India has formed a complete industrial system comprising industries such as nuclear power, electricity, electronics, energy, metallurgy, machinery, chemicals, textile, medicine, food, precision instrument, automobile, software, aviation, and space exploration.

Fourth, India’s developed IT industry helps sharpen the technological edge of its manufacturing industry. The country boasts a comparatively developed service industry, which occupies a significant position in its national economy. Thanks to its advanced IT industry, in particular, India has been dubbed the “world’s best back office.” After taking office in 2014, Prime Minister Modi has taken positive industrial policies to stimulate India’s economic and social development through promoting manufacturing and IT industries. The application of advanced information technologies has not only facilitated the optimal allocation and efficient operation of resources for Indian manufacturing enterprises, but also improved the economic returns and comprehensive competitiveness of its manufacturing industry. Furthermore, India pays great attention to the protection of intellectual property rights. As a result, many multinational giants including General Motors, Boeing, and Mobil have set up research centers in India.

Fourth, India’s developed IT industry helps sharpen the technological edge of its manufacturing industry. The country boasts a comparatively developed service industry, which occupies a significant position in its national economy. Thanks to its advanced IT industry, in particular, India has been dubbed the “world’s best back office.” After taking office in 2014, Prime Minister Modi has taken positive industrial policies to stimulate India’s economic and social development through promoting manufacturing and IT industries. The application of advanced information technologies has not only facilitated the optimal allocation and efficient operation of resources for Indian manufacturing enterprises, but also improved the economic returns and comprehensive competitiveness of its manufacturing industry. Furthermore, India pays great attention to the protection of intellectual property rights. As a result, many multinational giants including General Motors, Boeing, and Mobil have set up research centers in India.

Finally, English is the second official language of India, and a large amount of Indians have received English education, which makes it easier for the country to be integrated into the international community. India adopts a policy to promote elite education, so Indian senior executives are globally acclaimed for their extraordinary abilities, evidenced by the fact that Indians make up the largest proportion of foreign high-ranking executives in the Top 500 Companies of the United States.

A long way to go

Although India’s fast-growing manufacturing industry has drawn worldwide attention, it still faces many immediate challenges.

Strict labor regulations are a bottleneck that impedes India’s manufacturing development. At present, India has more than 50 labor regulations formulated by the Central Government as well as over 170 labor regulations enacted by local governments. Though these are for better protecting the rights of labor, the rigorous regulations, to some extent, block the development of India’s manufacturing. Prime Minister Modi called for a revision of the current Labor Act and suggested that factories with less than 300 employees no longer need government permission when they intend to cut jobs. However, the suggestion was met with objections from wide sections, which saw in it a violation of the interests of workers.

In 2014, two Toyota factories in Bidali shut down for 36 days following a strike arising from the Japanese automaker’s decision to lay off some 700 contract workers due to the rise in labor cost. This caused the company’s production capacity in India to drop by 40 percent, thus prolonging its product delivery period. In September 2015, a massive strike involving 150 million workers swept across India.

November 7, 2015: Employees work on the engines of Toyota cars inside the manufacturing plant of Toyota Kirloskar Motor in Bidadi, on the outskirts of Bengaluru, India. [REUTERS]

Moreover, India’s underdeveloped infrastructure cannot satisfy the demand of its manufacturing industry. Infrastructure in many parts of India remains in an elementary stage due to lack of funds over a long period, and this poor infrastructure has become a bottleneck which is impeding the development of the country’s manufacturing industry and is undermining the potential of the economy. With only three percent of its GDP invested in infrastructure construction, India has long suffered a fund shortage in the field.

In addition, the overall low education level of Indians results in shortage of high-end laborers in the manufacturing industry. Despite the fact that Indian elites are recognized internationally, the ratio of the population that has received higher education remains comparatively low, causing a shortage of qualified executives in its manufacturing sector. Meanwhile, it also lacks skilled workers. Considering that three-fourths of India’s population lives in the countryside, about 75 percent of the industrial workers come from rural areas. It will take time for them to become qualified, experienced workers.

In the short run, India’s manufacturing faces challenges greater than opportunities, and problems more than achievements.

Make in India: an opportunity or a challenge for China

Looking back upon the global shifts of the manufacturing industry, we can conclude that the world’s manufacturing center has consecutively moved from Britain, the United States, Japan, and Germany to today’s China.

Since China implemented its reform and opening up in the late 1970s, “Made in China” has shifted from imitation to innovation. In the process, the country has formed its own industrial and technological innovation system in a bid to become a great manufacturing power in the world.

Modi launched the “Make in India” program in New Delhi in September 2014. There is little possibility for “Make in India” to surpass “Made in China” in the near future. Even when India’s manufacturing industry grows big enough to compete with its Chinese counterpart, their competition will feature structurally differentiated development. The two will seek cooperation even while competing with each other

Modi launched the “Make in India” program in New Delhi in September 2014. There is little possibility for “Make in India” to surpass “Made in China” in the near future. Even when India’s manufacturing industry grows big enough to compete with its Chinese counterpart, their competition will feature structurally differentiated development. The two will seek cooperation even while competing with each other

Of course, the rise of India’s manufacturing industry will affect its Chinese counterpart.

First of all, some foreign investments will shift from China to India. The Indian government has eased restrictions on foreign investors and adopted a series of preferential policies to attract investments. This will help India transfer its low-end industries abroad and upgrade its position in the global industrial chain. Given the increasingly growing labor and land costs in China many labor-intensive companies that initially intended to invest in the country, such as Play-Doh, Monopoly, and Hasbro, have shifted their sights to India.

In addition, the rise of India’s manufacturing industry adds pressure on restructuring and upgrade of China’s manufacturing sector. Although it now contributes nearly 20 percent of the global manufacturing industry, China isn’t still a great manufacturing power. “Made in China” must shift to “Created by China”. In the process, China faces double pressures as high-end manufacturing is shifting back to developed countries and middle- and low-end manufacturing is diverted into other developing countries like India.

There are also positive factors, of course.

First of all, the “Make in India” program creates opportunities for Chinese enterprises to invest in India. Chinese companies can, on the one hand, explore the Indian market through establishing wholly-funded firms or joint ventures in India, and on the other, gradually transfer to India some of its excess industrial capacity in areas such as household appliances, communications equipment, and clothing, which have greater potential in the Indian market. Meanwhile, the “Make in India” program helps to relieve the trade imbalance between China and India. With the increase in the number and size of its manufacturing enterprises, India is expected to reduce its imports of Chinese-made industrial products, which will to some extent reduce India’s trade deficit against China.

Whether the “Make in India” program will go smoothly largely depends on the wisdom and capabilities of the Indian government. It is predictable that with the implementation of the program, foreign direct investments will further increase in India, and the country’s industrial structure will be further adjusted, and more job opportunities will be created, thus considerably expanding the global share of India’s manufacturing industry and accelerating the country’s economic growth.

Yang Wenwu, a Ph.D. in Economics, is vice director and a doctoral tutor of the Institute of South Asia Studies, Sichuan University and a council member of the Chinese Association for South Asia Studies.

Mukesh Kumar Verma is an Indian doctoral student at the Institute of South Asia Studies, Sichuan University.