Next-Level China-India Literary Exchange

On September 17, 2014, President Xi Jinping was invited to Gujarat, the hometown of Indian Prime Minister Modi. During their meeting there, Modi likened China and India to “two bodies with one spirit.” At the Indian Council of World Affairs the following day, President Xi remarked in his speech entitled In Joint Pursuit of a Dream of National Renewal that Modi’s words showed the kind and peace-loving nature shared by our two great civilizations and the intrinsic connection between them. “Two bodies, one spirit” inspires broad prospects for Sino-Indian spiritual and cultural exchange.

Culture connects many fields, with literature as the core and most powerful. Literature has always been the pioneering and key driving force of communication and exchange among cultures. China and India share a long and colorful history of literary exchange. Leading modern Chinese literary figure Lu Xun once offered a concise and insightful summary: “China has interacted with India since ancient days, and this process provided prosperity, thoughts, beliefs, morals, arts and literature. How much closer can two be than blood brothers?” In contemporary days, Indian literature, especially Tagore’s works, still exert far-reaching influence in China.

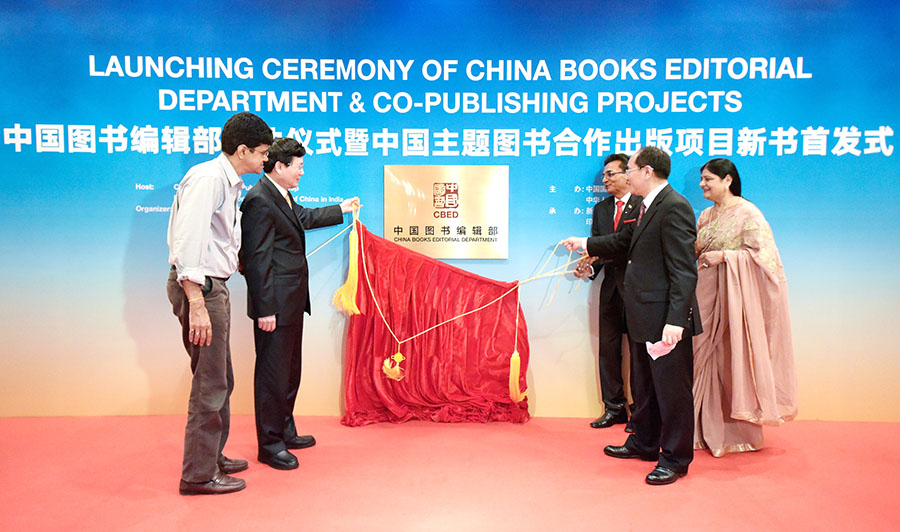

In April 2018, President Xi Jinping met Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India in Wuhan. Modi was in China for an informal meeting that produced several important points of consensus. On December 21, 2018, Indian External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj and State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi co-chaired the first meeting of the China-India High Level Mechanism on Cultural and People-to-People Exchange in New Delhi, India as a follow-up to the agreement made by Xi and Modi during their informal summit in Wuhan. By all accounts, literary exchange between China and India has entered a new stage. If we were engaged in “Version 1.0” Sino-Indian literary exchanges in the past, from now on, we should strive to build “Version 2.0.”

In the 1.0 era, Sino-Indian literary exchange was often spontaneous, one-way and only occurred between individuals. Confined by traditional means of communication, translations of literary works were done upon the initiative of individual translators. Members of translation groups were restricted to acquaintances. The two governments and scholars lacked dialogue. The only works available were paper publications translated without modern efficiency. Ongoing since the turn of the 20th century, it took 100 years for the Collected Poems of Rabindranath Tagore to be translated and published in Chinese.

Such roadblocks should be completely lifted in the 2.0 era, as the two governments increase support of literary exchange. Cultural enterprises have also pitched in on a large scale, and Sino-Indian literary exchange will soar with the new wings of science, technology and capital. Thanks to the latest intelligent translation software and 5G technology, translation of literary works will soon become industrialized. Translators can devote more time to error correction, polishing and improving the quality of translations. Alongside more available work in widely-read languages such as Chinese, English and Hindi, other tongues such as Bangladeshi and Tamil will get more attention. The context around media convergence, multimedia integration and cooperation will also encourage development of cultural undertakings and literary exchange.

Literary exchange between China and India has reached a new stage well worthy of investment.

Building a shared platform for literary exchange

Professor Tan Yunshan, who has traveled frequently to India for half a century, is a prominent friendship figure for the two Asian giants. With Tagore’s support, Tan Yunshan founded the Chinese Academy in Santiniketan in 1937. The institution remains a key research center of Sinology in India to this day. Over the past 80 years, the Chinese academic building has been regarded as one of the most spectacular architectural designs on campus. Increasing demand for Chinese language education has teachers and students of the Chinese academy seeking financial support from China to build a matching building for the original academic building as a special place for Sino-Indian literary exchange. Such a structure might include a small lecture hall, reading rooms and dormitories for Chinese teachers and language students. If a literature museum could also be built, it will be incredibly beneficial for teaching and studying.

New methods for classical translation

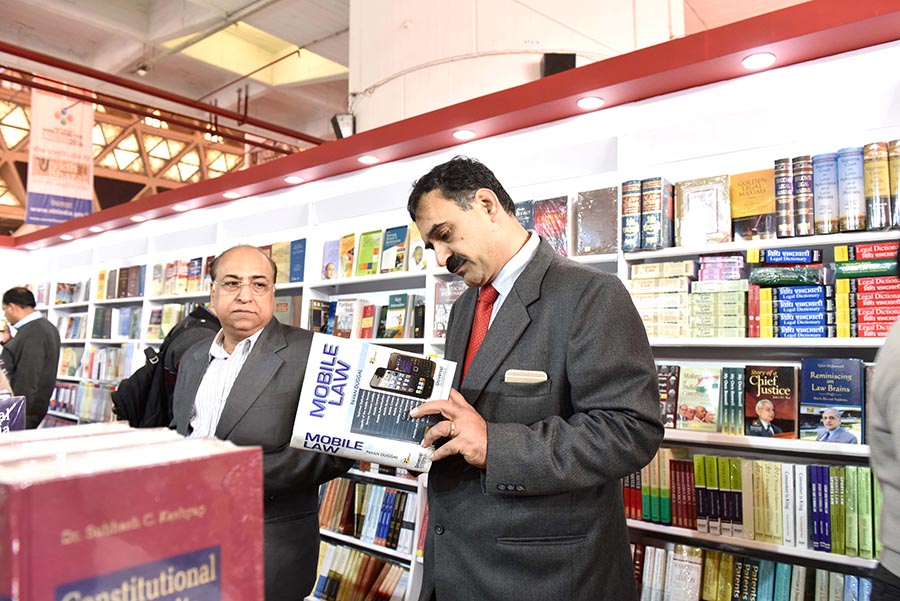

Translation of Chinese and Indian classics has always been an important form of cultural exchange and long-lasting. After an agreement on translation of literary works was reached between China and India in 2013, the Encyclopedia of China-India Cultural Contacts Between China and India was published in two volumes. During the same period, reciprocal translations of several classical works from the two countries accelerated. Among them were Hindi translations of Chinese Poetry, The Analects of Confucius and Four Books by B. R. Deepak of Jawaharlal Nehru University. Deepak also translated more than 500,000 words of Ji Xianlin: India-China Civilizational Dialogue and Intercultural Studies into English and Hindi. Few experts are as proficient in Chinese and Hindi as he is. Although direct translations from Chinese into Hindi are the most accurate, there are not enough translators to meet the actual demand. How could we change the phenomenon of “a roomful of Chinese translation of Indian classics and a handful of Indian translation of Chinese classics?” We could consider translating Chinese classics into Indian national languages such as Hindi from English versions. China and many other countries have used this “second-hand” option effectively. Today, Chinese, Hindi and English can be translated in parallel. Early Chinese translations of Tagore’s works relied on existing English and Russian translations and were only much later translated directly from the original Bengali.

Cooperate to protect classics

As a result of natural and man-made disasters, many volumes of literary classics have been destroyed in both China and India. Despite extensive efforts spent to rescue and protect literature today, arduous tasks in the field remain ahead. The Indian government now prioritizes a mission to save manuscripts. This project is significant for the preservation and documentation of ancient India, which held the tradition of “voicing religions.” China has rich experience and deep skills in rescuing manuscripts (including rare documents), which can be used for reference by Indian counterparts.

Literary exchange to film cooperation

Literary exchange could also be extended to film and television. A Sino-Indian co-production of Tan Yunshan would be a timely exchange project. If the film proves successful, three other works of a “Golden Bridge of Friendship” series between China and India could be co-produced: Tagore and China, Dwarkanath Kotnis and Ji Xianlin’s Passion for India. Historic works such as Xuanzang, White Horse Temple, Kumarajiva and Bodhidharma are some other subjects suitable for film and television.

Youth exchange and theatrical performances

Younger generations from China and India heartily appreciate each other’s literature. In addition to reading literary works and watching movies and TV, their enthusiasm has also been reflected in theater. Translations of classics have been the most valued, but touring performances also deserve attention. Tagore’s plays are popular among college students in Beijing, Tianjin, Jinan, Lanzhou and Shenzhen. The Ninth Beijing Nanluoguxiang Performing Arts Festival organized a season to pay tribute to Tagore with six plays: Chitra, The Post Office, Sanyasi, Red Oleander, Tan Yunshan and Atonement. Organizing Chinese and Indian university students to perform in each other’s countries might sow seeds for theatrical exchange.

Exporting tourism literature

Tourism is an important form of human communication, and tourism literature is a unique sector. China exports the world’s greatest number of tourists, and India attracts Chinese tourists with its Buddhist culture, splendid ancient civilization and Bollywood movies. China’s history and development also drew considerable tourism visits from India. The two countries need to deepen understanding of each other, and tourism should be a top action item.

The author is director of the Center for Indian Studies at Shenzhen University.