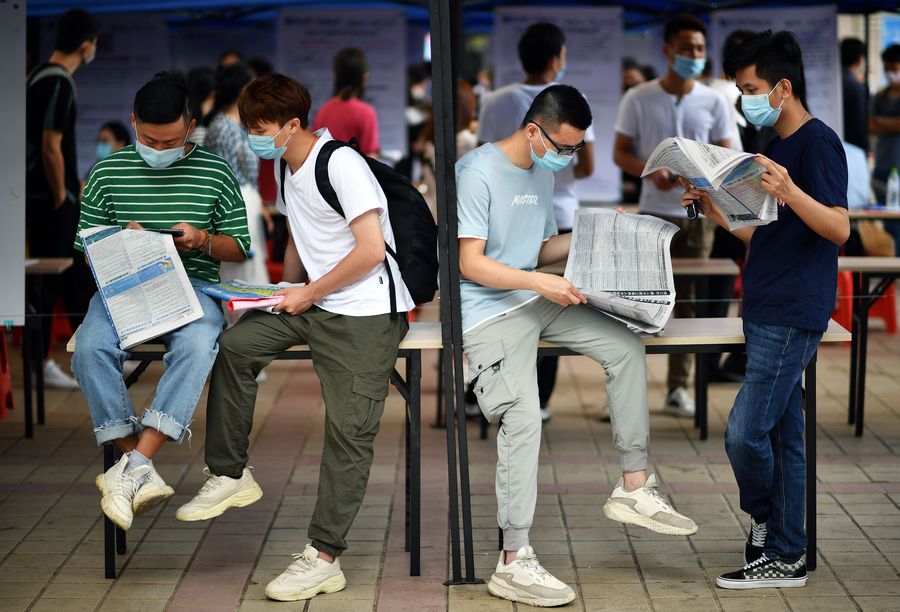

Ongoing Job Creation in China

In a modern economy, people need to bring in greater levels of income to send children to school, buy phones and computers, pay high urban rents, keep up with “respectable” fashion trends, and more. Being a small-time operator may mean a more relaxed pace of life, but it may also mean sleeping in your own store. Having a job in a larger company may grant a larger income, but it means living in a large city and working long hours dictated by a boss trying to force their employees to emulate the entrepreneurial origin stories of super-hard working business leaders like Jack Ma (founder of Alibaba) or Ren Zhengfei (founder of Huawei). How can China achieve the best of both worlds: both a good income and adequate personal time for everyone?

Creating jobs is a never-ending economic quest, especially in a country like China. In China, small businesses are a vital part of the economy, employing tens of millions. I’ve lived in China for several years, and all the small vendors of nearly the same merchandise have always puzzled me. How is it that they all sell the same stuff, with stores all right next to each other, and still make money? The truth is, there are customer networks that I don’t see. Urban population density is so much greater than the suburban reality that I am used to back in America that really there is a customer base, indeed several customer bases, to support the army of small shopkeepers in Chinese cities.

When I taught at an intensive English training program for Chinese English teachers, I was able to see one web of small businesses supporting (and supported by) the program I worked for. The shopkeeper of the small store on the campus where I taught had at least three customer bases: 1. the foreign teachers who didn’t want to walk far from the teacher dorms every time they wanted instant noodles or a soft drink; 2. the hundreds of students we cycled through every month with their daily needs; 3. whoever else was on campus. When our three-week monthly program ended, the store hours would be noticeably shorter.

Another small business that supported us was a small print shop. The regular demand for thousands of copies, print jobs, laminated class photos, passport photos for foreign teachers, and anything else we could think of – it all went through them. It was worth enough to that small print shop that they put a professionally made window decal on their shop door with the name of our teaching program so we could easily find them. There are thousands of small print shops like this everywhere in China, but this was the one I saw up close during my years teaching at this one training program.

Other small retailers include restaurants staffed by families from far western China, taking rotations at their family-owned stores in Beijing; shops and kiosks run by families who sleep in the same places they work; and more. In a way, creating these “jobs” is as simple as allowing individuals to take the risk to meet a need. It allows masses of people to sort themselves into economic niches rather than fretting as crowds over where their next meal will come from. However, jobs at this level do not easily translate into creating real companies with legal protection for growth into larger-scale businesses, nor do they support the moderate leisure required for an adequate family life.

A thousand years ago, life was lived a lot closer to home. Your work and your family life were much more integrated. The industrial revolution – indeed we are supposed to be on the “fourth” industrial revolution – has changed society so much that having a well-developed family life is almost something that only the wealthy can afford. New machines destroy occupations that had been radically innovative only ten years before. Workers have to reskill or upskill every five to ten years – or sooner.

Large companies work from profit motives. Profit is what they are there for. Some people found companies to change the world in a certain way, but in the end a company has to turn a profit. They go to where markets are, and they make investments that will turn profits. That often means passing over underdeveloped regions, unless there are essential raw materials present. Evening out job and opportunity creation requires some state intervention. The state, which encompasses the people and the government, is looking at the larger picture. Nothing should be out of balance: companies should not squeeze workers and communities for all they’re worth, and the state should allow market autonomy.

The state has the power to invest in development and it plays a different game than that played by companies. Companies by design seek their own profit; but the state must seek the welfare of the people as a whole, economically profitable or not. Western China has often been underdeveloped, except for where there were navigable rivers or easy land trade routes. Modern infrastructure allows rural populations to stay in their home regions and participate in capital-earning trades. The state formulates laws and policies and organizes the construction of railways, highways, bridges, dams, electricity generation, and other infrastructure besides. Internet connectivity theoretically allows small business owners in rural areas to find markets beyond their home villages and towns, attracting capital from big cities to small towns. In turn, rural consumption increases demand for industries from big cities.

Creating jobs in China is a multifaceted, multidimensional task requiring the precision of jewelers and the strength of giants. For China, both foreign investment and native industry have cooperated to modernize the economy and open new levels of employment never before available. The continual need to shape the economy for the entire nation will never end. Is everything in China the way I would choose for it to be? No, but I didn’t do the work to improve it, either. Neither China nor my home country is shaped without hard work, merely by my imagination. The important thing is that improvement continues and that the next year is a little better than the last year. China has figured out enough to get itself this far, and as paradigms shift and realities change, it will have to figure out something else. As for the near future, I think that 2021 has a good chance of being at least a little better than 2020.