The Endless Search for Fang Dazeng

At 8 o’clock on the morning of December 12, 2016, having traversed the whole of Beijing City, Feng Xuesong, a TV producer and documentary director, finally arrived at the Liangxiang Campus of Beijing Technology and Business University. It was the 14th leg of the campaign “Fang Dazeng on Campus,” and also the final leg of 2016.

Initiated by Feng Xuesong, “Fang Dazeng on Campus” is a charity event, which aims to visit 20 Chinese universities to display Fang Dazeng’s life and China’s history in his times. The tour began in September 2015 and will run until July 2017, the end date marking both the 80th anniversary of the Lugou Bridge Incident (also known as the Marco Polo Bridge Incident), launched by Japan in July 1937, and also the 105th anniversary of the birth of Fang Dazeng.

Since the end of 1999, Feng has been “looking for Fang Dazeng” in all kinds of ways. He has looked up historical documents, visited Fang’s old friends and returned to the last places mentioned in reports by Fang. Feng has not missed anything about Fang and has done almost biographical research on him. “Looking for Fang has been the most time-consuming task of my career,” claims Feng. “I won’t stop until I find him.”

Why Look for Fang?

On July 7, 1937, Japan began its full-scale invasion of China by launching the Lugou Bridge Incident, on the outskirts of Beijing. Three days later, Fang, then 25 years old, rushed to the battlefield with his camera. On August 1, as fighting against the Japanese aggressors continued on Lugou Bridge, a 7,000-word article under his pen name “Xiao Fang” was published in World Affairs, a magazine founded by the Communist Party of China in 1934. This was the first article to cover the battle with both text and pictures, making Fang the first correspondent ever to report on the Lugou Bridge Incident.

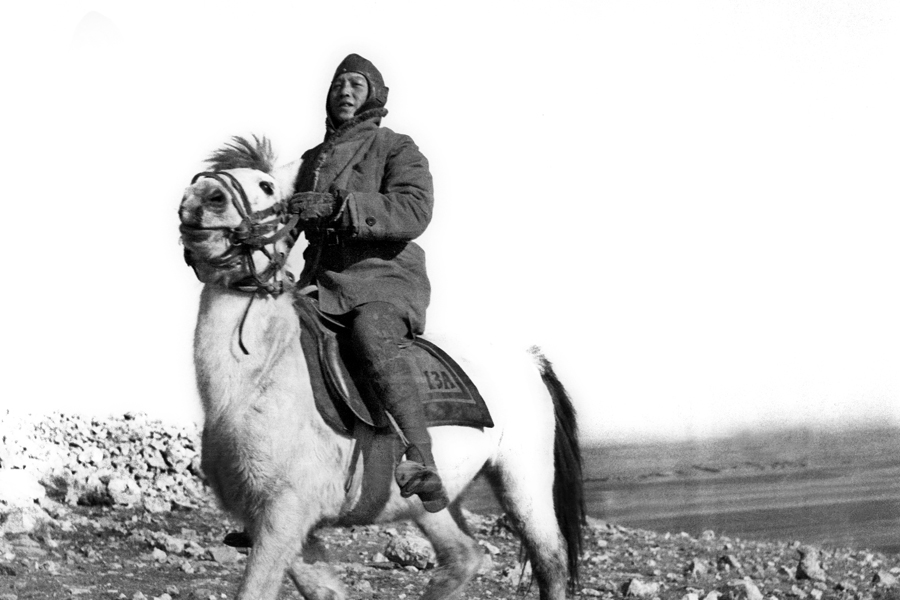

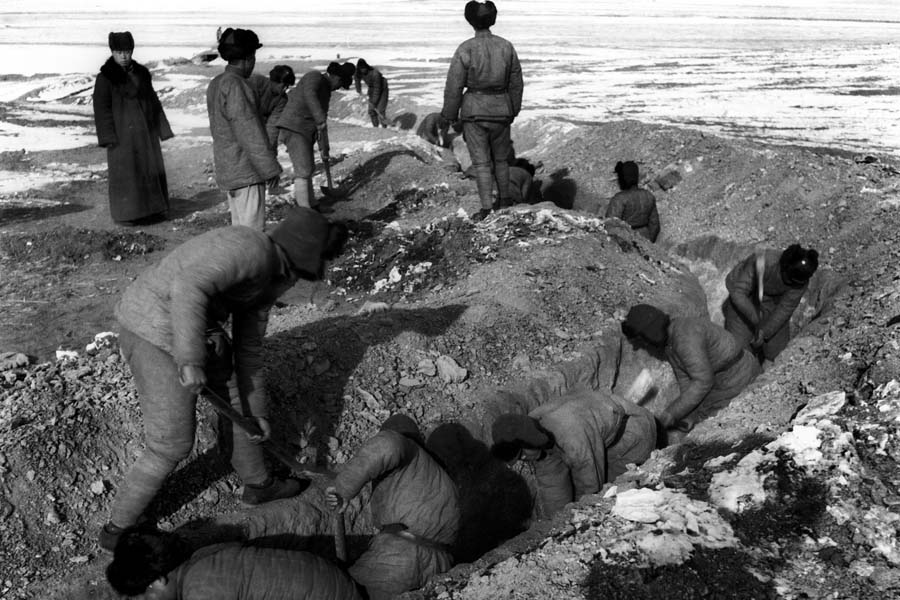

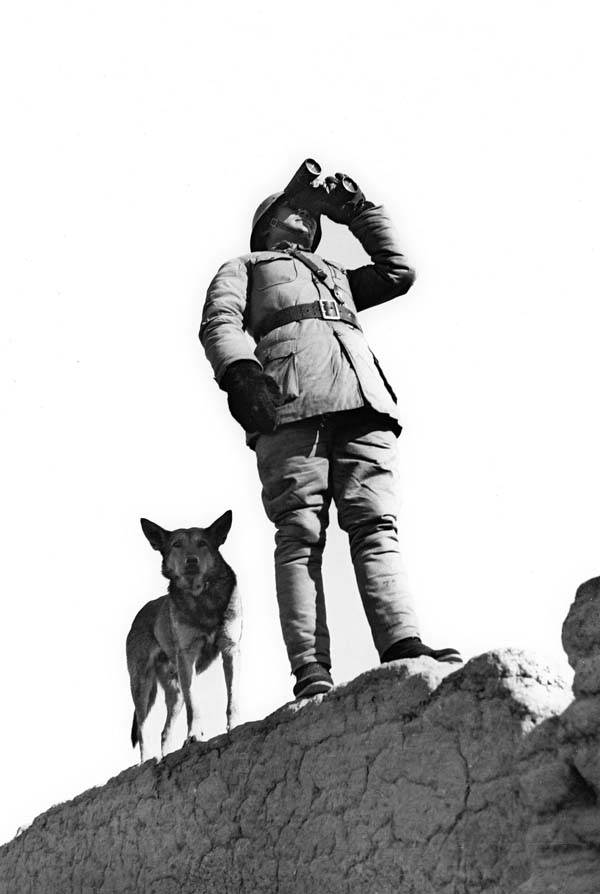

In 1936, when Japanese troops attacked China’s Suiyuan region, Fang, then a photo correspondent with the China and Foreign Journalism Society, contributed a number of news photos and articles from the frontlines. The articles, with their many photos, showed skillful writing and close observations, creating precious records of the Suiyuan battlefield. However, Fang went missing after his last battlefield report on Ta Kung Pao on September 30, 1937.

In 1999, in his office, Feng Xuesong stumbled across a fax note from the China Photographers Association, asking if they could co-compile Fang’s works into a book. Words such as “China’s Robert Capa” and “mysterious disappearance” on the note caught Feng’s attention. It was at that moment that Feng embarked on his journey of “looking for Fang Dazeng.”

Feng went to Fang Chengmin, the younger sister of Fang Dazeng, who provided him with 837 photos taken by her brother. Intrigued by the precious historical moments recorded by Fang, Feng began to look into the periodicals and newspapers from between 1934 and 1937 stored in the National Library of China. It took Feng four months to find Fang’s articles and pictures in these publications, including Fighting against the Japanese Aggressors on Lugou Bridge, The 29th Army: Fighting for Our Country, Air Raid Drill in Jining, and Wanping County Under the Gunfire of Japanese Invaders. From then on, more and more traces of Fang’s work as a war correspondent gradually emerged.

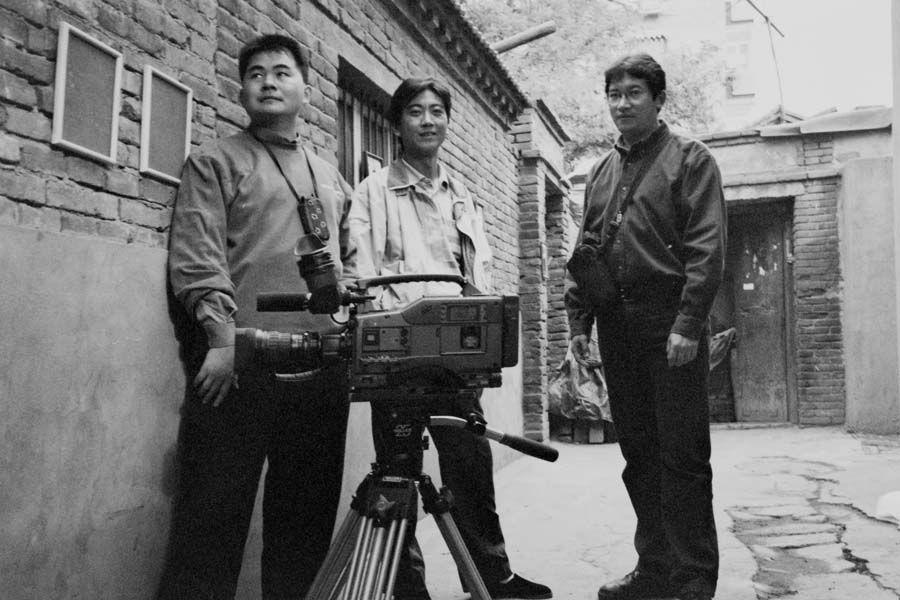

Later, Feng visited various places Fang had once frequented, including cities like Baoding, Shijiazhuang, Taiyuan, and Datong. Within eight months, Feng interviewed around 100 civilians who had experienced the Chinese People’s War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, as well as scholars and specialists, and filmed more than 40 hours of footage. On November 8, 2000, the first Journalists’ Day since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Feng’s documentary Looking for Fang Dazeng was broadcast on China Central Television.

While filming the documentary, Feng uncovered more evidence of Fang’s valuable qualities: his vision of news, his professionalism and his patriotism. In the decade that followed, Feng searched for information and friends of Fang, and retraced the final steps mentioned in Fang’s news reports to seek every possible clue connected to him.

In 2014, Feng Xuesong compiled the historical materials he had found, along with his experiences from the search, into the book Fang Dazeng: Disappearance and Reappearance. “Feng’s book reveals the stories of Fang Dazeng, a distinguished journalist and photographer who had been buried in oblivion for over 80 years,” says Fang Hanqi, a leading Chinese scholar of news history. “Making his name known to the public is a great contribution to the research on China’s history of journalism and war photography.”

The Memory Won’t Fade Away

Fang was famous before he vanished, but his disappearance, combined with the turbulence of the time, drowned out both him and his works. A major publication on the history of China’s photography includes just a 100-word description of him. Thanks to Feng’s search over recent years, public knowledge of Fang’s life has been enriched.

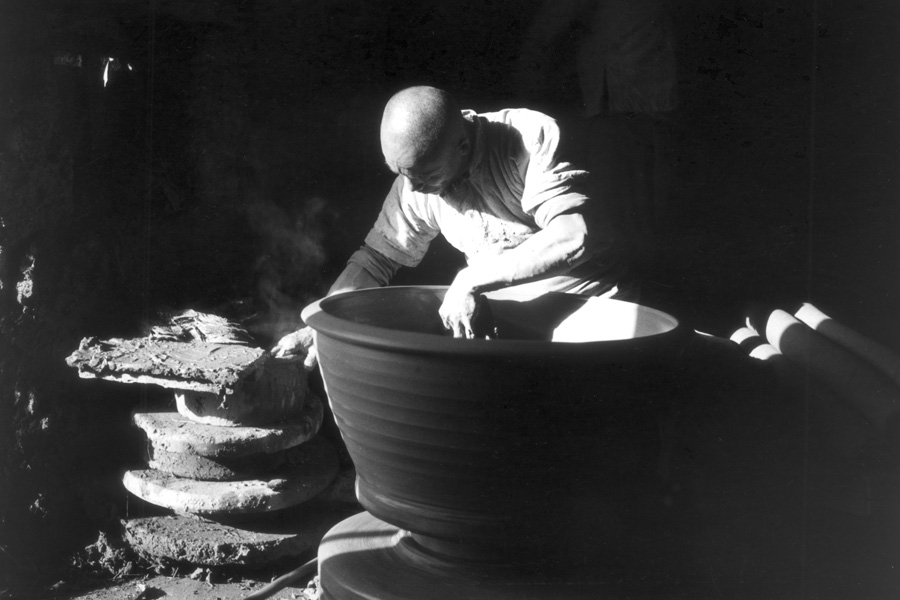

Fang was an excellent war correspondent and photographer. But before turning to battlefields, he once recorded people’s lives in Tianjin City and Shanxi Province with his camera. His attention to ordinary laborers and underprivileged people is also of significance.

The figures seen through his lens include rickshaw pullers at the entrance of a hutong, local people in ragged clothes, boat trackers at a wharf, and laughing kids. Those pictures show not only the wartime lives of people in the 1920s and 1930s, but also a trust and equality between the subjects and the photographer.

In 2006, Fang’s relatives donated his 837 surviving original photographic plates to the National Museum of China. In 2015, Fang’s photographs of the battlefields were exhibited in the museum to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the victory of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression.

In the history of Chinese photography, many of the most precious images were taken by foreign photographers, such as famous French photographers Henri Cartier-Bresson and Marc Riboud. The absence of Chinese photographers has always been a pity. But Fang’s return to prominence fills this blank. Despite the poor conditions of his times, Fang intuitively injected a rich sense of empathy and a great deal of fun into his works, and whether intentionally or accidentally, created a record of his times.

In the years since the publication of the book Fang Dazeng: Disappearance and Reappearance in 2014, a “Fang Dazeng” craze has spread through China’s academic and media circles, with various events organized to remember and study him. A symposium on Feng Xuesong’s tracing and collection of Fang’s stories was held by the All-China Journalists Association; the Fang Dazeng Memorial was established in Baoding, Hebei Province; and the “Fang Dazeng on Campus” publicity campaign has been started, influencing an increasing number of college students. Still, Feng has more plans, such as adding Fang Dazeng into the Encyclopedia of China, setting up a Fang Dazeng Fund, establishing the Fang Dazeng Award to encourage young journalists, and adapting Fang Dazeng’s stories into a drama.