What Made China-India Border Impasse?

On April 20, 2016, Indian National Security Advisor Ajit Doval visited Beijing to attend the 19th Special Representatives’ Meeting (SRM) on the China-India Boundary Question together with Chinese State Councilor Yang Jiechi. This was the second Special Representatives’ Meeting that Doval participated since Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi began his tenure.

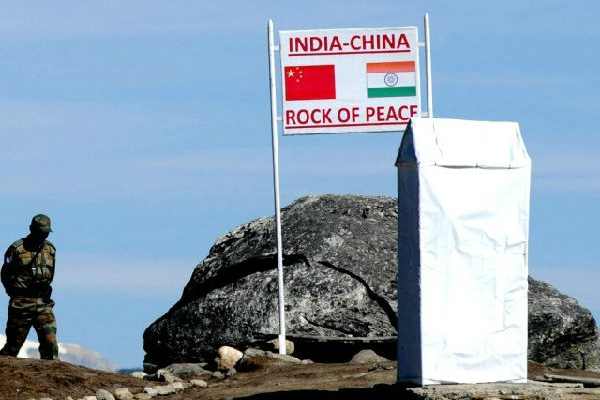

Of all its terrestrial neighbors, China has yet to complete border demarcation with India and Bhutan. To some extent, the boundary demarcation between China and Bhutan depends on how China and India solve their border disputes.

Missed Opportunity

Border issues are not all of China-India relations, but they are the crux that impacts bilateral relationship. In his recently-published Strategic Dialogues: A Memoir of Dai Bingguo, former Chinese State Councilor Dai Bingguo revealed the origin and evolution of the SRMs on the China-India Boundary Question, as well as key factors behind their border impasse.

In fact, China and India once lost a good opportunity to settle their border disputes.

During his visit to China in June 2003, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, then prime minister of India, proposed to then Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao that the two countries depute special representatives on border issues who could directly report to them, so that the Indian side could get rid of the negative effect arising from its inefficient bureaucratic system.

After the establishment of the SRM mechanism, both Prime Minister Vajpayee and Special Representative Brajesh Mishra showed the political will to solve border disputes with China and their plan for taking pragmatic decisions in the matter.

Unfortunately, Vajpayee lost the 2004 parliamentary election. His successor, the Indian National Congress (INC) lacked willingness and capacity to solve China-India border disputes with any urgency.

Thornier than Expected

Even so, China and India signed the Agreement on the Political Parameters and Guiding Principles for the Settlement of the India-China Boundary Question, which set a “three-step” roadmap: First defining the guidelines for the settlement of border disputes, then formulating a framework agreement on implementation of the guidelines, and finally completing border demarcation. Thereafter, the SRM mechanism seemed to enter a stage of aimlessness.

China and India have major differences on how to interpret the so-called “political parameters and guiding principles.” Moreover, the Indian side lacked political decisiveness to settle the China-India border disputes. As a result, the SRM has gradually become an annual high-level meeting that merely aims to maintain a negotiation channel and a friendly atmosphere.

The SRMs are no longer focused on border issues between the two countries, but also discuss topics including border peace and stability, and even regional and global issues. To some extent, the SRM mechanism has become an “upgraded version” of a China-India Strategic Economic Dialogue (SED). (Meanwhile, the two countries have set up a ministerial-level SED mechanism).

The two countries established the Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination on India-China Border Affairs in 2012, and signed the India-China Border Defence Cooperation Agreement in 2013, both with an eye on maintaining border peace and stability.

All of these indicate that the settlement of China-India border disputes is harder than expected.

China and India have spent half a century seeking solutions to their border disputes: As early as 1960, then Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai and Foreign Minister Chen Yi visited India for a negotiation on border issues. Later, the two countries launched three rounds of working group meetings. From 1981 to 1987, they held eight vice foreign ministers’ meetings. Then, from 1989 to 2005, China and India held 15 vice ministerial-level working group meetings.

In the process, the two sides have already discovered each other’s bottom lines. It is known that what is now required for a solution is both sides making up their mind to settle the border disputes, which particularly depends on India’s attitude.

Five Outcomes

Despite that fact that China-India border disputes remain unsettled, there are still some outcomes achieved over the decades. After all, the two countries have reached consensus on the basic roadmap for settlement of their border issues, which is specifically reflected in the Agreement on the Political Parameters and Guiding Principles for the Settlement of the India-China Boundary Question that was reached in 2005.

After more than five decades of negotiations, China and India have reached a general consensus on the following:

Seeking a package settlement of China-India border disputes. That means the solution to China-India border issues will be full and final at one go, and the two sides won’t seek any “early harvest” or “phased settlement.” This is because China holds that there are disputes on the eastern section of its boundary with India, while India holds that disputes exist on the western section of their boundary. So, the problem will be solved only when the two sides negotiate on the basis of seeking a package settlement for disputes on all sections of their boundary line.

Settling border disputes through political means. The talks held when late Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai and Foreign Minister Chen Yi visited India in April 1960 proved that the two countries couldn’t solve their border disputes based merely upon historical traditions or international law. In deference to objective facts and historical factors, the only solution is political negotiation. For instance, the fourth article of the Agreement on the Political Parameters and Guiding Principles for the Settlement of the India-China Boundary Question stipulates that the two sides will give due consideration to each other’s strategic and reasonable interests, and the principle of mutual and equal security.

Following a “three-step” roadmap to solve border disputes. The joint statement signed by China and India during Modi’s China visit in May 2015 reaffirms the commitment to “abide by the three-stage process for the settlement of the boundary question, and continuously push forward negotiation on the framework for a boundary settlement based on the outcomes and common understanding achieved so far, in an effort to seek a fair, reasonable and mutually acceptable solution as early as possible.”

Settling border disputes through negotiation. For both countries, this point speaks for itself. On the one hand, it has been proven impossible to settle border disputes by force and arms or through wars; On the other hand, the aftermath of a war between the world’s two major emerging powers is unimaginable.

Following the principle of disconnecting the overall development of China-India relations from the settlement of their border disputes. The principle is the most highlighted part of the new model of China-India relations. In 1988, when Rajiv Gandhi visited China, the two countries agreed to decouple their border disputes from the development of their bilateral relations. The first article of the 2005 Agreement on the Political Parameters and Guiding Principles for the Settlement of the India-China Boundary Question stipulates that the differences on the boundary question should not be allowed to affect the overall development of bilateral relations. Prime Minister Modi reiterated the principle when he visited China in 2015.

The author is associate professor at the Institute of International Relations of China Foreign Affairs University and a research fellow in the Collaborative Innovation Center of South China Sea Studies at Nanjing University.