Wuzhen: Venice of the East

It’s hard to beat the magic of a boat cruise down an ancient waterway alongside fishermen rowing into the setting sun. Waterfront houses with flower gardens greet passersby navigating under crescent-shaped bridges crossing the canal as dusk engulfs the final moments of the day.

Such a spectacle heralded the beginning of my summer journey through a wonderland of traditional Chinese crafts, museums and folklore in Wuzhen.

A wooden house facing the water caught my attention, reminding me of a navigational canal called Nallah Maar that my grandfather often mentioned in his tales. That canal, which was the lifeline of old Srinagar, connected a lagoon to the famous Dal Lake.

Archived images of the canal show tourists flocking to the waterway and boatmen offering rides on the crystal clear water past rows of old Persian style houses with flowerbeds.

Stories of the canal, which was gone by the time I was born, mesmerized me as a child. My stroll through Wuzhen awoke those childhood memories that had long been hidden under a pillow.

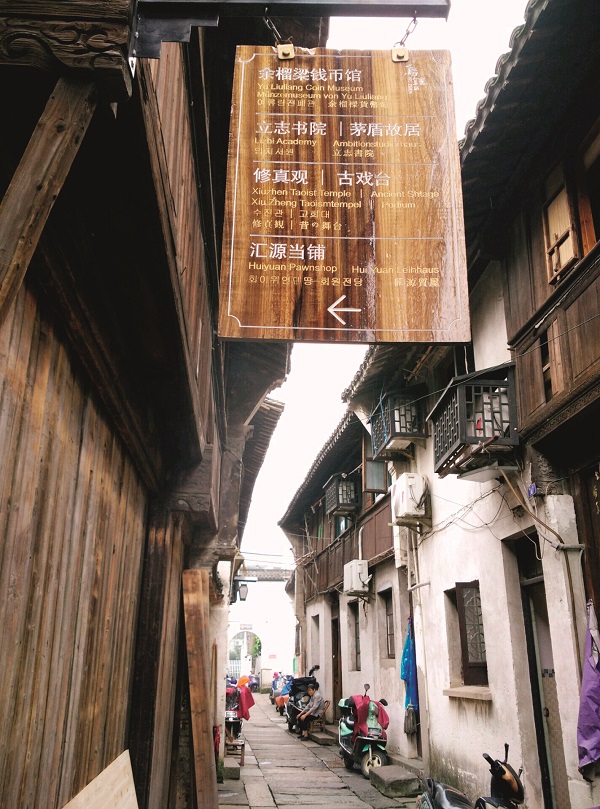

Located at the center of the six ancient towns south of the Yangtze River, 17 kilometers north of the city of Tongxiang, Wuzhen displays China’s history via ancient stone bridges, stone pathways and delicate wood carvings.

Renowned Chinese writer Mao Dun was born in Wuzhen, and his best-known work, Lin’s Shop, describes the life in the town.

Wuzhen is divided into six traditional districts: workshops, local-styled houses, culture, food and beverage, shops and stores, and the customs and life district. A tourist boat took me through the magical town, and I spotted an architectural marvel: “Bridge within a Bridge.” The serendipitous attraction was born of two ancient bridges that can be seen through each other’s arch. Another example of innovative architecture is the Moon Bridge, which is designed to evoke the full moon. These bridges look especially beautiful under moonlight, when the night sky reflects off the water underneath.

Later, I found myself fascinated by a shadow play performance, a form of traditional Chinese art. Performers tell entertaining stories by projecting characters made of sheep or cattle hide onto a white screen. They control the puppets with bamboo sticks, creating lifelike action in the shadows.

While walking past a plethora of museums and craft shops, I saw a traditional Chinese cobbler working on the roadside. Based on the piles of heeled stilettos, resoled boots and polished loafers, it seemed that he had a lot of work, but the wrinkly cobbler was happy to entertain my uninvited attention.

Like a generous tourist, I put my shoes on his anvil and asked him to polish them. To strike up a conversation, I asked him how business was.

“The days when I was too busy for chitchat are gone. Now I have plenty of time,” he replied.

He told me that he once handled 100 repair jobs a day as he rubbed his wretched old brush against my brown oxfords, turning them into a shiny mirror.

“Five yuan,” he said politely.

I took out a 10-yuan banknote from my wallet, handed it to him and rushed out. As I left, he stared at the banknote with a familiar smile.

China is anything but ordinary—I found a museum dedicated to beds! The Ancient Bed Museum at Dongzha Street is China’s first devoted to the collection and display of antique beds.

A framed bed with hoof-shaped legs and rails like brushes caught my eye. “Bed of a Thousand Craftsmen” is a beautiful piece of workmanship from the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). As its name indicates, it took over a thousand craftsmen three years to make the bed.

At the Museum of Foot Binding in Wuzhen, artifacts and photographs privy to the painful pursuit of the “three-inch lotus,” a euphemism for the bound foot, were on display. In ancient Wuzhen, as well as the rest of China, foot binding was a controversial custom practiced for over 1,000 years.

It houses 825 pairs of shoes designed to bind female feet as well as numerous pictures and other relevant items.

While ancient stone bridges, stone pathways and delicate wood carvings flavor Wuzhen’s legacy, Nallah Maar has been relegated to fossilized remnant of erstwhile prosperity that Srinagar once enjoyed in the pristine past.

It’s heartbreaking to imagine the canal being filled in the 1970s to make way for a road through the old city after the arrival of motor transport.

My greatest takeaway from my stay in Wuzhen was realization that in the ancient water town built around a series of canals over 1,300 years ago, very little has changed. The place has been carefully restored and masterfully renovated.

The author is a journalist of the Press Trust of India.